Oft mentioned, Little Known

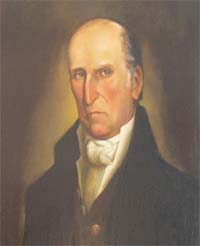

I have profiled a few of the "second-tier" First Patriots, those who played important but less widely celebrated roles in the American fight for independence. This blog examines one such individual from the British side. While researching the background of the Yankee Doodle Spies, I noticed that the name Alexander Leslie appeared more often than others. His name came up in battles and campaigns from New York to the Carolinas. I started to wonder about this man, who seemed to lead troops and be involved in the most interesting places but never quite became a household name like Simon Fraser or Banastre Tarleton.

|

| Alexander Leslie |

Before the outbreak of War

Alexander Leslie, son of the Earl of Leven and Melville, joined the army in 1753 as an ensign in the Third Foot Guards. By 1768, he had become a lieutenant-colonel of the 64th regiment, stationed in Boston. His rapid rise in rank reflects Britain's extensive military commitments during that period of warfare. Leslie served with the British garrison at Boston before the outbreak of hostilities in 1775. Before the American War of Independence began, he led troops on a mission to Salem, Massachusetts, to search for contraband weapons, including cannon, held by the Patriots. A confrontation—not physical—with rebels at a raised bridge disrupted the mission and delayed his advance. His force was eventually allowed to proceed into Salem, but they found nothing of importance and retreated. An early version of Lexington and Concord was narrowly avoided. One wonders if a more hot-blooded commander might have produced a different outcome. It is said that a spy provided Leslie's commander, Gage, with faulty intelligence.

|

| The Retreat at Salem Bridge |

Mostly success in the North

|

| Leslie's Light Infantry led the night movement that cut off a large part of the rebel army on Long Island |

By the New York campaign of 1776, he became a brigadier-general. He led troops on Long Island, at Kip's Bay, and at Harlem Heights. Leslie commanded a brigade of Light Infantry, elite soldiers skilled at fighting in America's fields and forests. Men who could shoot, move, and fight better than most. His brigade formed the advanced guard of General William Howe's strategic night envelopment of Washington's forces. The Light Infantry seized the strategic Jamaica pass at night and led a nighttime advance that cut off a large part of the American troops. Leslie's command suffered 63 casualties for their efforts. This was a relatively small number for such a critical and successful action, but it mirrored the casualties of other brigades that fought during that hot day near Brooklyn. However, when the British took New York, Leslie's Light Infantry was mauled by Colonel Thomas Knowlton's Rangers at the Battle of Harlem Heights. Unfortunately for the American cause, Knowlton was mortally wounded. Much of this is captured in book one of "Yankee Doodle Spies," The Patriot Spy.

|

| Battle of Harlem Heights |

When the British landed north of New York in October 1776, Leslie's command was once again in the fight, but he suffered heavy losses at the Battle of White Plains. The solid and steady Leslie missed a chance to earn glory at Princeton in January 1777. General Washington had escaped the British under Lord Cornwallis through a night march around the British left toward Princeton, which was several miles behind Cornwallis. Leslie commanded the brigade garrisoning Maidenhead (today's Lawrenceville, NJ). Lord Cornwallis ordered Leslie and Mawhood's brigades into action. But before Leslie could get involved, the vanguard of the Continental Army broke through Colonel Mawhood's brigade and took Princeton. The Continental Army escaped Cornwallis and found safety behind the Watchung Mountains at Morristown. Leslie also took part in the siege of Charleston as commander of the combined brigade: four battalions of Light Infantry and elite Grenadiers, the best of the British troops. When Charleston fell, Leslie initially took command of the city. He stayed there only a few weeks. Once he had organized the garrison, General Henry Clinton ordered him back to the main British garrison in New York, where he took command of the Light Infantry and Grenadiers stationed there.

|

| Washington leads the attack at Princeton |

Struggling in the South

In the autumn of 1780, Clinton sent Leslie to the Chesapeake Bay leading an expedition aimed at distracting American forces and then capturing the supplies the Americans had gathered for their defense. Leslie reached Virginia in October but soon received orders from Cornwallis (who was now under his command) to proceed to Charleston. Leslie likely realized that Virginia would be critical to the war's successful ending, so before heading south, he sought confirmation from Clinton. His correspondence indicates he was reluctant to go south. Before leaving Virginia, he wrote Clinton expressing hope that "you will be able to take up this ground; for it certainly is the key to the wealth of Virginia and Maryland." Nonetheless, he headed south. Leslie arrived in Charleston in mid-December and received orders to march inland and meet up with Cornwallis's army. Cornwallis decided to wait for Leslie to reinforce him before moving to join forces with Banastre Tarleton. That decision proved a critical mistake. Due to bad weather, Leslie's force only reached the main army camp on January 18, one day after the Battle of Cowpens. Tarleton then had to face Daniel Morgan's division without support from Cornwallis, whose presence might have turned it into a British victory instead of a decisive defeat.

|

| The Cowpens |

Leslie's command accompanied Cornwallis's forces in pursuit of General Nathanael Greene's army. At Guilford Courthouse, he commanded the British right in a style Cornwallis praised in his follow-up dispatch: "I have been particularly indebted to Major-General Leslie for his gallantry and exertion in the action, as well as his assistance in every other part of the service." Leslie took part in the challenging march north from the Carolinas into Virginia, one of the remarkable feats of the war. However, Leslie was not with Cornwallis at the siege and surrender of Yorktown. By the summer of 1781, his health had declined to a point where Cornwallis transferred him to Charleston, from where Clinton recalled him to New York.

But the stay in New York was short. On August 31st, Clinton ordered him to sail once again to Charleston and take command. After Cornwallis surrendered at Yorktown, Clinton placed Leslie in charge of all British forces in the South. The weather and stress of command took a toll on Leslie. He had a bad fall from his horse that weakened him and complicated his other health issues. Recognizing his poor health, he asked to return to New York, but Clinton could not spare him. He remained in command throughout the rest of the year despite numerous requests to be relieved due to worsening physical stamina and stress management. Leslie had worked in America for years, his wife was dead, and he had a daughter he wanted to see and ensure a good marriage for. He suggested several suitable replacements, but Clinton, although claiming sympathy, delayed and stalled his requests.

| After the British took Charleston, it became the "Green Zone"of the southern theater |

Frustrating Finish

So Leslie soldiered on, supervising the decline of British interests in the south. After the treaty, he organized the consolidation and removal of British garrisons while dealing with relentless rebels, disheartened troops, and complaining Loyalists. These groups watched in disbelief as their birthright and lives evaporated, as the British withdrawal from Charleston approached. In the end, Leslie's command in Charleston outlasted Clinton's stay in New York, which the new British commander-in-chief, General Guy Carleton, would have the honor of evacuating. Gradually pulling back the British inland garrisons from outposts, maintaining order, and repelling rebel attacks was a difficult task that offered little glory. The time in Charleston would have drained even a strong man. The southern rebels were among the most active throughout the war, engaging in bitter small-scale fighting, property theft (by both sides), and general chaos. As thousands of Loyalists moved into Charleston (another kind of "Green Zone,” like New York), the challenge of caring for civilians became overwhelming. Leslie's attempts to arrange a cease-fire of sorts went unanswered by the Americans, who now sensed blood and always suspected British traps. Leslie remained in command of the city until it was finally evacuated in December 1782.

Back (at last) to Britain

Leslie, who would remain a widower his entire life, returned to Scotland in 1783. On a happy note, he was able to witness his daughter Mary-Anne's wedding in 1787. According to accounts, Leslie was well-liked by his peers and considered genteel and mild-mannered by most. His life after America is surprisingly obscure, given that he was appointed deputy commander of the forces in Britain. In 1794, he was near Glasgow, Scotland, where he led troops to suppress a rebellion by the Breadalbane Regiment of Fencibles. Some reports claim he was hit by a stone while marching some of the prisoners away and died shortly afterward. However, at least one eyewitness account disputes that and points to a Major Leslie as the victim. Regardless, the quiet and easygoing Scot died in December of that year. His death was, like his army career, unannounced and little noted. Yet the stalwart Scot should not be dismissed lightly. He served honorably through great hardship and, unlike many of his contemporaries, with little regard for his own glory.

.jpg/1024px-Het_verbranden_van_de_Engelse_vloot_voor_Chatham_-_The_Dutch_burn_down_the_English_fleet_before_Chatham_-_June_20_1667_(Peter_van_de_Velde).jpg)