Old Hickory

A key event in my historical novel, The Lafayette Circle, is General Lafayette’s visit to The Hermitage, the plantation home of Andrew Jackson, leader of the War of 1812 and the Seminole War. On May 25, 1825, Jackson meets Lafayette and his entourage at their steamer and gives them a tour of his house. While there, Jackson displays an exquisite pair of matched pistols.

“Do you recognize these, sir?”

“Indeed, sir.” Lafayette choked up and warmly embraced his host.

Lafayette had given the two “saddle pistols” to Washington in 1778—during the middle of the American War for Independence.

When Washington died in 1799, his nephew inherited them and later gifted them to William Robinson, who further gifted them to the Indian Wars and War of 1812 hero—Old Hickory.

A poignant moment for the two veterans of the American Revolutionary War—although Old Hickory was more of a young acorn during the eight-year struggle. In fact, he was just a teen when the war exploded across the Carolinas.

Young Hickory

Andrew Jackson and his two older brothers grew up on a hard-scrabble piece of land in the Waxhaws region, nestled along the border of the two Carolinas. The family was of the flinty Scots-Irish stock who provided many of the early settlers, carving out a living in the New World—stubborn, resourceful, resilient, fearless, and defiant. Sadly, Jackson’s father, Andrew Senior, was killed while felling a tree just three weeks before Andrew’s birth—his mother and two older siblings raised him.

Southern Strategy

War initially pushed into the Carolinas—British attempts at a naval invasion were blocked until Savannah fell, which then created a southern land and sea route to Charleston. Militias and Continental troops under American General Benjamin Lincoln fought back against British forces led by General John Maitland in the summer of 1779. During the British rear-guard action at Stono Ferry on June 20, Andrews’s older brother Hugh, who was badly wounded, died from the heat and exhaustion.

However, within a year, a large British Army led by Sir Henry Clinton captured Charleston, and Clinton deployed General Charles Cornwallis and notorious Colonel Banastre Tarleton to conquer the rest of the state. War was heading to the Waxhaws.

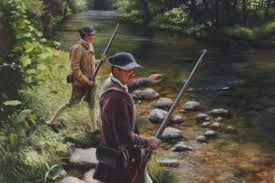

Rebel Teens

Defiant, the two younger Jacksons joined Colonel William Richardson Davie's regiment, serving as couriers. They participated in the short but bloody clash against a British outpost at Hanging Rock on the Catawba River on August 6, 1780. Davie launched a diversionary attack there to support General Thomas Sumter’s larger assault on Rocky Mount, just west of the initial site. Davie’s initial attack failed, but Sumter redirected his efforts and launched a more significant attack with several regiments.

But a year later, 14-year-old Andy and his 15-year-old brother, Robert, were fleeing after their unit was surprised and scattered by Tory war parties that had joined with the British to eliminate any remaining resistance. Over a third of their comrades were caught in the sweep, but the Jacksons tried to avoid that fate.

However, hunger dictated otherwise. After hiding their horses and weapons in the woods, the boys approached a friendly farmstead, the home of patriot Lieutenant Crawford. Local Tories spotted the horses and warned the British. While supper was on the stove, a party of British soldiers surrounded the Crawford farm and stormed the house. They searched the house with a fury only imaginable during a violent civil war. Clothes torn from dressers are ripped to shreds, furniture is chopped up, and pots and dishes are smashed. Oaths and threats filled the air.

The British commander stormed across the room and accosted the younger Jackson. He pointed to his mud-spattered riding boots. “Boy! Clean my boots!”

Andrew straightened and lifted his chin in defiance. “Sir, I am a prisoner of war and should be so treated.”

Enraged, the dragoon officer drew his sword and delivered a slashing blow that sliced through the young teenager’s raised wrist to the bone, then slid off and struck his forehead. It left a scar he carried for life. It also left an even deeper scar on Andrew’s mind—an indelible hatred of everything British, which became one of the main motivations of his life.

The officer turned on Robert. “Then you clean my boots!"

When he defiantly refused to obey, the blade came down, striking him on the head and sending streams of blood down his face.

The boys, badly wounded and bleeding, were force-marched in oppressive heat to a prison camp at Camden, where they joined some 250 other captured rebels. They were left untreated, given little food, and suffered cramped quarters. Then, disease struck as it usually did in filthy prisons. Andre had to listen to the heart-wrenching moans of men suffering from smallpox. Eventually, the affliction struck Robert. Andy, too, was lying in bed, suffering malnutrition that was sapping his life from him.

Mother’s Love

During a prisoner exchange, Elizabeth, the boys’ mother, arrived in Camden. She argued for the release of her two sons. As the two appeared near death, her request was granted. While Robert struggled on the single horse, Andrew endured the forty-five-mile journey home to Waxhaws.

Back home, Elizabeth struggled to restore her boys' health, but Robert died within days. Desperate, she worked tirelessly to help Andy, and he gradually recovered. His days of fighting were over—in this war. Elizabeth and other women began nursing other prisoners and traveled to Charleston to assist those suffering on prison ships in the harbor. Surrounded by disease, she contracted cholera and died just before Charles Cornwallis surrendered his army at Yorktown.

Badge of Honor

Andy’s wound healed, leaving him with a scar across his brow. The cut on his forehead left an even deeper scar on Andrew’s mind—his hatred for all things British. It also served as a living memorial to his family, who sacrificed so much for the cause, as well as to the soldiers who suffered and died.

The fiery teen Andy Jackson grew into Andrew Jackson—a man of action who led American soldiers to victories over the Creek Indians, the Spanish, and notably the British. He secured extensive territories in Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi, and crushed enemy lines of redcoats at the Battle of New Orleans, a win that established the United States as a nation to be reckoned with.

No comments:

Post a Comment