Bennington, New York (Vermont)

A volley of musket fire suddenly sprayed just over their heads, and, contrary to tradition, training, and inclination, both officers ducked.

His jaw stiff with determination, Friedrich Baum rose to his feet and pointed his saber in the direction of the rebel fire. "The Iroquois must have fled. Why else would we receive rebel fire from there? Move a platoon to the south. Then bring up the cannon and quickly before they overrun us."

"We are already low on ammunition," said Glich.

"Then bring up the last caisson. No sense saving powder now."

Excerpt from The North Spy

This edition of the Yankee Doodle Spies features another profile of a character from my upcoming novel, The North Spy, Oberstleutnant Friedrich Baum. Since very little is known about Baum's background, I will need to fill in some gaps with speculation.

Professional Soldier

Friedrich Baum commanded a rare commodity in North America—a cavalry regiment. In this case, it was the Dragoon Regiment Prinz Ludwig, better known as the Brunswick Dragoons. The regiment's name came from its benefactor, Prinz Ludwig Ernst, the younger brother of Duke Karl, who ruled Brunswick. The Prinz Ludwig regiment was one of seven hired by the King of England from the Duke of Brunswick. The other six were infantry units: four musketeer regiments, one grenadier regiment, and one jaeger regiment. The Duchy of Brunswick (Braunschweig) is a northern German principality that provided a skilled professional army to allies like Prussia or generous supporters like Britain.

A Storied Regiment

The regiment was established in 1688 and was officially classified as a dragoon regiment in 1772. It was made up of four troops at full strength, totaling 330 officers and enlisted soldiers. These impressive horse soldiers wore bicorne hats and bright blue jackets, armed with carbines and sabers. Although they carried swords, dragoons were mounted infantry who rode into battle and dismounted to fight as infantry with light muskets or carbines. It was assumed that the unit would need their horses while in Canada, but they did not, and later many swapped their heavy boots for shoes with black gaiters.

Typical of the time, the commander was a colonel who did not actually lead the unit—Oberst Friedrich von Riedesel. Instead, the lieutenant colonel (Oberstleutnant) was in command. Von Riedesel was later promoted to major general and given command of the entire Brunswick contingent, which was "leased" to King George to serve as auxiliaries to the British Army during the American Revolutionary War under the 1776 treaty between Great Britain and the Principality of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel.

Vague Origins

Friedrich Baum was born in 1727, but his exact birthplace is unknown. Little is known about Baum's background, but he was a tough, professional officer from the small principality ruled by Friedrich Graf zu Schaumburg-Lippe-Bueckeburg. Young Baum rose to become captain of the Graf's Carabiner Corps, an elite troop unit. He fought in some battles during the Seven Years' War in Europe but had little battlefield command experience before serving in the American Revolution.

A New Allegiance, A New World

Baum transferred his service to the Duke of Brunswick in 1762 and, by 1776, had become a lieutenant colonel. Baum and the Brunswick Dragoon Regiment left the German duchy in February 1776 as part of two Brunswick divisions hired to fight the United States under the now General Friedrich von Riedesel.

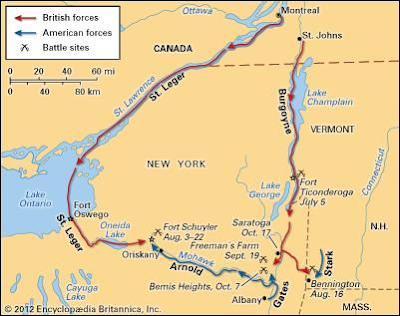

After arriving in Quebec, the Brunswickers assisted Governor Guy Carleton in policing the Americans who were struggling to retreat to New York. In the summer of 1777, Baum's regiment was assigned to the army of General John Burgoyne, which was preparing for an important campaign in the Lake Champlain region of New York.

Northern Invasion

The invasion began in late June and started strongly with a quick advance along Lake Champlain, capturing the large Fort Ticonderoga through a surprise attack and pursuing the rapidly retreating rebel army. However, by August, Burgoyne's forces started to slow down and become exhausted in dense, difficult terrain. More critically, the supply line became overextended, and the army ran out of supplies. Intelligence reports told Burgoyne that Loyalists were rallying to the king and that livestock and food were only a few miles away at Bennington in the New Hampshire Grants – a disputed area stretching between New York and New Hampshire that would later become Vermont.

A Special Mission

Burgoyne ordered Baum to lead 800 men through the Grants, seize cattle and horses, and rally the many Loyalist sympathizers in the area. Baum's men marched east on August 11, 1777. Additionally, his force, which included over 374 Brunswick Dragoons, about 50 Jaegers, 30 artillerymen, along with 300 Loyalists, Canadians, and Indians, set out on what was expected to be a straightforward mission.

True to his Seven Years War experience and European training, Baum moved slowly through the rough, wooded terrain. He would occasionally stop the column to dress the ranks and realign them. But time was not a major concern, as Baum was told. The numerous Loyalists in the area were expected to rally to him. Unfortunately, word of the Iroquois attacks on the settlers had the opposite effect. Loyalists did not show up, but the Patriots were rallying.

Rebel Resistance

This became clear the next day when a group of rebels engaged Baum's column in a firefight at Cambridge. His "spider-sense" tingling, the cautious Baum sent Burgoyne a request for reinforcements. He also expressed frustration that Loyalist bands had not rallied to him as he expected. What to do? Dig in, of course. He had his men build several redoubts east of Bennington and waited for reinforcements and for the situation to unfold.

Rising Tide

Unfortunately, his redoubts were so spread out that they could not support each other. Although some Loyalists had come into his camp to join his column, there were rebel spies among them. Two American forces were also preparing to attack Baum's exposed position. The spies soon relayed details about Baum's defenses. About 2,000 rebels, mostly New Hampshire militia under John Stark and Seth Warner's Green Mountain Boys, were ready to strike against Baum's positions. Stark pushed units around Baum's flanks and nearly surrounded him, and on the morning of August 16, Stark ordered the attack.

Shock and Awe in the Grants

The veteran Baum was caught off guard by the speed and shock of the rebel attack. The Brunswick Dragoons and other Germans fought back fiercely, skillfully using their redoubts. But they fell for a trick by Stark, who deliberately sent units out to draw the defenders' fire and deplete their scarce powder and balls. When the defenders' volleys began to weaken, the Americans advanced and took the redoubts one at a time.

Last Redoubt

Baum, commanding the last stronghold, assessed his situation. The rebels swarmed and peppered them with constant fire. The air hummed with the sound of musket balls, and the hollering of angry rebels fired up for the final attack. Most of his Loyalist and Indian allies had fled. It was down to him and the dragoons. The professionals who had followed him across the deadly battlefields of Europe and across a vast ocean now faced a land and a people even more threatening.

Desperate Gambit

With ammunition nearly exhausted, surrounded, and outnumbered three to one, our brave dragoon recognized his dire situation and resorted to a desperate measure. His remaining dragoons drew their long sabers. Although they had no horses, they had gravity! Blades shining in the sun, the tall, mustached warriors in pale blue charged downhill at the startled Americans. Seven brave dragoons fought their way out and eventually limped into Fort George. Sadly, our brave dragoon was not among them. Oberstleutnant Braun took a musket ball, was captured by the rebels, and died in the American camp on August 18.

Battle Lost

The final musket shots fell silent at dusk. The anticipated reinforcements, a force of Brunswick jaegers and grenadiers under Lieutenant Colonel Heinrich von Breymann, arrived too late to turn the tide. Some accounts say Breymann disliked Baum and moved at a pace of less than a mile an hour, but the terrain and other factors could explain this. Breymann himself would be killed in action a few months later - shot by his own men! Yes, "fragging" was a real thing in the 18th century and throughout military history.

Campaign Lost

The impact of Baum's defeat cannot be overstated. Over 700 soldiers from Baum's command were either taken prisoner or reported missing—almost the entire force. American casualties numbered around 70.

The failed expedition meant Burgoyne lacked enough food, supplies, and draft animals for the ongoing fight at Saratoga—not to mention the absence of a corps of professional soldiers. The Indian allies lost confidence in Burgoyne's chances of success and began to drift away, leaving Burgoyne without native "cavalry" to scout and screen in the vast New York wilderness.

And, of course, Baum's defeat was the precursor to Burgoyne's army suffering a more important loss two months later at Saratoga, turning the tide of war in favor of the Americans.

Legacy

So our bold dragoon's legacy is not a good one. Baum's first experience leading an independent command became his last. He did his duty, but his mission failed. Still, our bold dragoon gave the last full measure. I believe, in some way, as a professional officer, he might have preferred to give his all than face the shame of defeat at the hands of rebels.

They buried Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum on the north bank of the Walloomsac River, though the exact spot is unknown. He died in a nearby house that was torn down around 1870. A marker placed at the site of the house in 1927 by the Sons of the American Revolution serves as the only connection to the man whose death may have marked the start of a turning point in the American War for Independence.

_Herzog_zu_Braunschweig_-_Wolfenb%C3%BCttel_-_Bevern.jpg)