Frontier Savagery

The sound of frenzied whooping mixed with shrill screams filled the ears of the three frightened boys huddled together for safety. Their hands and feet were bound, leaving them helpless to do anything but stare with eyes stinging from tears. Soon, the crackling of flames began to compete with the savage whoops of the Delaware braves, who grew more excited as the burning fires crept up the figure tied firmly to a pole. Some of the braves shouted what could only be taunts and insults, primarily because the old man remained stiff-lipped as his flesh began to sear and burn, emitting a putrid stench that made the three youths nauseous while exciting the bloodlust of their tormentors. Finally, the fire completely engulfed the old man, whose head slumped as the dark smoke swallowed him.

One of the

boys shouted when the smoke cleared and the fires subsided, revealing a pile of

charred wood and bone, "Grandpa!"

"Don't

let 'em know you're scared," hissed Simon, the oldest. "Never!"

After this, fourteen-year-old Simon Girty and his two brothers were soon parceled out to different tribes as hostages. This was a typical sequence of events for families who settled along the American frontier, which was Indian territory.

Frontier Family

Simon Girty was born in 1741 in Chambers Mill, Pennsylvania, a small hamlet near Harrisburg in the heart of the colony. His Scots-Irish family later moved to Sherman's Creek, about thirty-five miles to the northwest. In 1751, Girty lost his father, who was killed in a liquor-fueled duel. Girty's grandfather raised the boys. Girty and his brothers grew up illiterate but tough, as the family lived on the edge of civilization.

Backwoods Homestead

The West Aflame

In 1754, war reached Pennsylvania as France and England fought one last time to control North America. Along the frontier, groups of Indians and their French allies raided farms and settlements, causing a wave of terror.

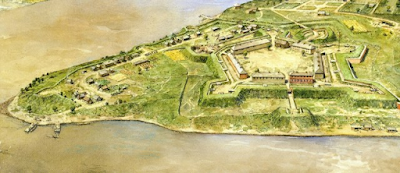

In 1756, the Girty family and many others, afraid of falling prey to the tomahawk, fled to the safety of Fort Granville, a small stockade about fifty miles northwest of Harrisburg. A mixed force of French troops and Native Americans, mainly Lenape warriors, attacked on August 2. The garrison quickly surrendered; the fort was destroyed, and the Girtys and other settlers were taken captive. But before they were forced to move off to live with new masters, they had to watch as their grandfather was burned at the stake.

Indian Life

Simon was captured by the Delaware tribe but was later handed over to a band of Seneca, who marched him to the Ohio Territory, where they "adopted" the young man into the Seneca nation. As was often the case with white captives, Girty quickly adjusted to life among the native tribes, learning their language and customs. He soon began to learn Iroquois and the subtleties of tribal life and warfare.

Frontier Freedom

Girty was finally released at Fort Pitt in 1759. By then, he had become fluent in the Seneca and Iroquois languages and was well-versed in all aspects of tribal life. And, most importantly, Indian warfare — a Seneca in all but skin color.

Girty returned to live with his mother and worked as a struggling farmer. He also served as an interpreter for fur traders dealing with the Delaware Indians in western Pennsylvania. The British authorities valued his skills and enlisted him to negotiate treaties with various tribes along the frontier.

During Lord Dunmore's War against the Shawnee Nation in 1774, Girty became a skilled frontier scout. There, he befriended Simon Kenton, a well-known frontiersman.

War for Independence

When war broke out between Britain and her American colonies in 1775, Simon supported the patriot cause. General James Wood sent him back to the Ohio Territory, where he helped with American negotiations with the Shawnee, Seneca, the Delaware, and the Wyandot.

Troublemaker

Girty struggled with military discipline, often finding himself in trouble with the officers in charge. This issue reached a peak in September 1777, when he was arrested and accused of treason, as he was suspected of helping to plot the seizure of Fort Pitt.

Local Loyalists plotted to kill the occupants of Fort Pitt before surrendering it to the British. Girty was acquitted, but the experience left him bitter, and he switched his allegiance back to the crown. In March 1778, the frontiersman Girty, along with his brothers James and George, quietly slipped out of the fort and traveled to Detroit, the main British base in the northwest.

Indian Department

There, British Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton recognized the need for Girty's skills as a linguist and frontiersman and ordered him to join the Indian Department, where he quickly gained notoriety across the northwest frontier.

Backwoods Pirate

From that time until the war ended in 1783, Simon Girty attacked the Americans. His cultural and language skills helped him recruit many native tribes to the British side and also kept them from supporting the Americans. He led or directed raids, ambushes, robberies, and outright massacres, becoming the terror of the West. Frightened settlers started calling him The White Savage or The Great Renegade.

First Blood

His true entry into chaos began in 1779 when Girty, leading mixed groups of Loyalists and Indians, carried out several attacks that left the patriots shaken. He unleashed Indian war bands around Fort Laurens, Ohio, where they massacred multiple patriot units. His October 4, 1779, ambush of an American column led by Colonel David Rogers was a brilliant strike against the cause, resulting in fifty-seven militiamen dead and the capture of 600,000 Spanish dollars.

In 1780, Girty helped British Captain Henry Bird lead a major attack against American settlements in Kentucky. The mission led to the capture of two forts and over 300 hostages, including his former friend Simon Kenton, whose release he arranged.

The Great Renegade

By this point, the Americans had branded Girty a turncoat — offering a reward of 800 dollars for him, dead or alive. The incendiary Girty even succeeded in angering arguably the most prominent Loyalist, Iroquois war chief Joseph Brant, by confronting him when Brant was bragging. The equally fiery Brant slashed Girty across the face with his saber, leaving a wicked Al Capone-like scar. Ironically, the mutilation gave Girty much prestige among the braves.

Campaign of Infamy

In June 1782, Captain William Caldwell and Simon Girty led a force of 400 warriors from the Wyandot, Lenape, and Shawnee tribes, along with a detachment of Butler's Rangers, against a group of 500 volunteers commanded by Colonel William Crawford. They stopped the American push aimed at destroying Indian settlements on the Sandusky River. Then they surrounded Crawford's force, which retreated in a disorganized panic.

They captured many prisoners, including Crawford, who endured brutal torture for days before being burned at the stake. Like his grandfather, Girty was said to have stood by without intervening, gaining lasting infamy among Americans on the frontier. However, some accounts say he was threatened with his own scalping if he interfered.

Kentucky Killing

Caldwell, Girty, and the mixed band brought chaos into Kentucky, launching brutal attacks on many defenseless farms and small villages. This campaign of terror reached its peak after their failed siege of Bryan's Station on August 15. When he learned of an approaching relief force, Girty and his band decided to use a trick. As the column drew near, they pretended to retreat.

Girty positioned several of his braves along the bluffs overlooking the Blue Licks River. He kept them in plain sight, aiming to lure the Kentuckians into a kill zone. Caldwell placed most of the rangers and warriors in ravines and behind boulders.

The trap was set.

One of the column's leaders, renowned frontiersman Daniel Boone, suspected a trap and warned for caution, but the column's commander, Major Hugh McGary, hurried his men straight across the stream. Boone said, "They'd all be slaughtered," but took his command to the right of McGary's line, which then moved right into a deadly ambush.

No Post-War Pause

The Treaty of Paris did not reduce the tension between the northwest tribes and the ever-expanding American settlements that started to cross the frontier. Girty also played a part. For the next ten years, he was a relentless supporter of war against the Americans at tribal councils. Was it driven by his deep hatred for his former countrymen, revenge for past wrongs, or simply because he was an agent of British policy? We may never know. But it was probably all of those things.

War Drums Along the Miami

By 1791, the tribes of the Ohio country had unified into a federation that vowed to fight the American threat to their lands or die trying. The gathered warriors had all the traditional cunning, skill, and bravery of their ancestors but also had British training and weapons that made them a much stronger force than any of the Western tribes that gained fame in the next century. Still, many leaders decided to settle with the new government, but American raids and the killing of Chief Little Turtle's daughter pushed the tribes into war.

An Army's Destruction

Simon Girty was with Chief Little Turtle of the Miami and his war party when they defeated an American Army led by Revolutionary War heroes General Arthur St. Clair and Richard Butler at the Battle of the Wabash. The northwest was vulnerable to the war bands. Enraged, President Washington ordered the formation of a new army, called the American Legion, and placed it under the command of a war hero from eastern Pennsylvania, General

Anthony Wayne.

Fallen Timbers

Simon Girty marched to confront this new army alongside War Chief Blue Jacket and his Shawnee, Ottawa, and various other tribes. In August 1794, Blue Jacket and Girty faced off against Wayne's American Legion and General Charles Scott's Kentucky Militia at Fallen Timbers. In the brief but decisive battle of Fallen Timbers, Anthony Wayne defeated Blue Jacket's coalition, and the tribes ultimately sued for peace — a bitter pill for a noble people.

Escape North

The British finally evacuated Detroit in 1795. The long-standing Great Lakes bases used for operations against the new American government were handed over to the Americans by the Jay Treaty. Still a wanted man, Girty had to move north to safety in Canada and worked for the British Indian Department in Amherstburg, Ontario. The elderly Girty, now nearing depression and struggling with alcoholism, had to flee the town when the Americans invaded in 1813. He returned after the Americans withdrew and lived there until his death on February 18, 1818.

Pantheon of Savagery

What can we understand from this controversial frontiersman? For one, he had many companions in the pantheon of savagery, from all backgrounds and sides. Besides the well-known battles on the Atlantic coast, the American War for Independence was both a civil war and a clash of cultures. The hundreds of raids, ambushes, and small skirmishes were much more brutal than the European-style battles in the east. Simon Girty represents the many men on both sides who used savagery as a weapon of war. Sadly, this pantheon continues to grow with new members to this day.

.jpg)

This is a fascinating story that captures the interwoven intrigue and blunt brutality of the era. Too often the rearview mirror of history is over simplified to white and black hats. Send this to teachers around the country. Many (most) schools barely touch, or accurately depict, this pivotal era of frontier history.

ReplyDeleteThere is so much we don't know about frontier life in American history. Thanks to those who research and educate us about life in this time period.

ReplyDelete