The key rattled in the cell's lock. "It's time, almost noon," said the Sergeant of the Guard.

The prisoner rose from the musty cot and followed the escort out of the red brick jailhouse building to the town commons, where a large crowd of spectators awaited the condemned. The last fourteen days had been a whirlwind of intrigue, missteps, apprehension, and cross-examination. Now, the condemned man gazed at the simple noose that would, momentarily, squeeze the life from him—for he was a confessed spy.

"Does the prisoner have any last words, Sergeant?" asked the officer in charge.

"No, sir," replied the sergeant.

"I believe my statement to the examiner at my trial amply provides my last words, sir," said the prisoner." I only ask they be made public after my sentence is carried out."

The officer nodded, and a soldier threw a cord noose over his shoulders.

From Cold Winter to Warm Spring

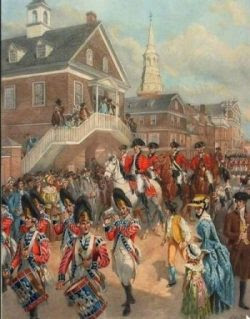

The winter of 1777 was one of savage warfare—a struggle for the necessities of survival for two armies desperate to feed their men. But by March, General William Howe, the British commander in New York, was setting his sights on another try at the American capital in Philadelphia—even as London had dispatched a large Army to strike deep into the colonies from Canada that summer. So, while paying lip service to the British Minister for the Colonies, Lord George Germain's strategy, Howe was plotting a move south and an assault on Philadelphia from the mouth of the Delaware River. But to do this, he needed intelligence—and something more.

No Man's Land

While the Americans held Philadephia and General George Washington's Continental Army encamped at Morristown, central Jersey became a no man's land of foraging parties, raiders, thieves, smugglers, and spies. The former colony was flush with Loyalists, as was the area around Philadelphia. Not yet a year old, the cause of liberty was not in every American's heart. There were plenty of high and low-born people who were willing to support the King, especially if there was some coin involved. Both sides had networks for spying and striking out against their enemies. One such network within the new nation's capital was active in helping prepare the way for the return of the British.

Spy Highway

James Molesworth was a member of that spy ring. Born in Staffordshire, England, Molesworth made his way to America and established himself in the New World, eventually as a Clerk in the Office of the Mayor of Philadelphia. Like so many, Molesworth remained Loyal and got involved with their spy network in and around the capital. Molesworth agreed to go to New York and meet with the British authorities.

The Loyalists had a sort of "Underground Railroad" to make their way past American patrols and sentries into the occupied City of New York. Molesworth traveled into the Jerseys with an accomplice named John Caton, who went by the alias of Warren. Warren took him to Bullions Tavern, where they met another accomplice named Smith, who guided them to Milestone Bridge. From there, the two slipped past rebel pickets and entered British lines. Molesworth met with Pennsylvania Loyalist leader Joseph Galloway, who recommended him to General Howe, who gave Molesworth a lieutenant's commission. Howe needed his services back in The City of Brotherly Love.

The Mission

Howe was planning a sea-borne attack on Philadelphia by sailing up the mouth of the Delaware River. He knew from spies and other informants that the Americans had several forts positioned there and had embedded Cheveaux de Frise-like traps along the riverbed. These were rows of long spikes with points hidden below the water level that could rip open the hulls of British warships.

The British instructed Molesworth to recruit sympathetic Delaware pilots to exfiltrate them north to New York and guide the British fleet around the traps. Howe also questioned him about the forts and the armed galleys used by the Americans. Although the British provided him with no cash, he was told to spare no expense in finding a couple of pilots. He was also to arrange for sabotage and other mayhem in preparation for the British attack.

Philadelphia Ring

On his return, Molesworth approached several Loyalist sympathizers—clearly, they had a network well in place. He met a Mr. Sheppard and a Joseph Thomas. He connected with his other accomplices—a Clerk in General Mifflins's Office named Collins, a Clerk in the City Vendue Office named Keating, and a Livery Stable owner named Sheppard. At least two women were involved as well—a Mrs. Abigail McCay and a Mrs. Sarah O'Brien. The latter two had been actively feeling out (they used the word "tampering") Delaware pilots for a special mission and had a few they thought might agree to the enterprise. One, named John Eldridge, refused to go. However, another, Andrew Higgins, agreed and was able to bring another, named John Snyder, into the plot.

Clandestine Meetings

Mrs.McCay was Molesworth's intermediary with Mrs. O'Brien, and it was at her boarding house that Molesworth finally met with "agreeable" pilots at seven in the evening. Although promised great rewards for their service, Molesworth could only offer fifty pounds, which he had gotten from Sheppard. Molesworth schemed to get horses from Sheppard's Livery and ride north.

Sheppard, the livery owner, approached a farrier named Fox for a horse, but none was to be had that night, and it was decided that looking for a third horse at that hour might draw suspicion. Molesworth, instead, would travel the next day. But there was no next day's travel. Someone blew the whistle. For want of a horse...

Court Martial and Sentencing

Molesworth was arrested and faced a trial by court martial presided over by General Horatio Gates. Witnesses were questioned from 25 through 28 March. Molesworth gave his own testimony on the 27th. The court martial convicted the spy on the 29th, and after Congress confirmed the sentence, Molesworth was hanged in the Philadelphia Commons on 31 March 1777.

General Horatio Gates

Justice for All?

But what of the others? Collins, Keating, and Sheppard escaped to British-held territory, eluding the pursuit by provosts under a captain named Proctor. According to General George Washington's report, it was the pilots who turned Molesworth in. But who? Eldridge? Higgins? Snyder? Or some combination? My take is Eldridge, with the other two plus two ladies providing testimony in exchange for leniency. For his part, Sheppard made his way to New York, where he served as a pilot for the eventual British move on Philadelphia in the fall of 1777. For his services, Sheppard received the lucrative post of Deputy Commissioner of Forage during the British occupation.

Justice for No One?

Years later, the infamous General James Wilkinson commented on the case in his memoirs. He alleges there had been no legal basis for a military court martial, and the political pressure on Gates for a swift outcome led to a conviction with a unanimous verdict. A conviction Gates and Congress swiftly approved. Wilkinson claimed to have met with him in his cell, offering mercy if he would give up his accomplices—Molesworth refused.

No Peace for the Dead

Molesworth remained controversial, even in death. His body was relegated to a potter field—a burial ground for the indigent. Local Loyalists seethed (secretly) at the affront. When the British occupied Philadelphia later in the year, a group of Quakers had him exhumed and interred in a Quaker cemetery. Now, the local patriots seethed (secretly). When the Americans re-occupied Philadelphia in 1778, you guessed it, Molesworth's now rather tired corpse was once more exhumed and reinterred in the potter field.

Culper Prelude?

The British network in the heart of the capital sent a visceral chill through the Americans in the City, the Continental Army, and Congress. Had it remained undetected, it could have proven a more effective network than the celebrated Culper Ring in New York. Perhaps that explains the quick justice and burial. It might also have shaped General George Washington's thinking on espionage and the need for ultra-tight security and compartmentalization, as intelligence and espionage played an increasingly important tool in the struggle ahead.

No comments:

Post a Comment