A Hard Land to Travel

America during the time of the Yankee Doodle Spies was a tough land to travel through. Most of America was still heavily forested and inland, with rugged to mountainous terrain making travel dangerous and often life-threatening. By the mid-1700s, however, the coastal and tidewater regions were relatively developed. Here, a network of mostly poor roads crisscrossed these areas, connected by fords, bridges, and ferries crossing waterways.

Early American bridge building was limited to short spans, and fords only allowed crossing shallow waters. Numerous ferries were established along rivers and tidal areas, carrying carts, wagons, livestock, and travelers on foot, horseback, or in carriages.

However, ferries during the Yankee Doodle Spies era were often unreliable and sometimes dangerous. With no weather forecasting, they were vulnerable to sudden storms, weather changes, and shifting tides that could cause accidents, property damage, and injuries to passengers or animals. Many ferries kept irregular schedules, with some only operating part-time, making the service unreliable and often a poor source of income.

Consequently, many ferry operators had second jobs, such as farming, running a tavern, or owning a store. Schedules were frequently nonexistent, leaving weary travelers at the mercy of the ferryman's other commitments, which could lead to delays and long waits.

|

| Dutch settlers used ferries to traverse the Hudson and cross to Long Island |

But they were vital to the transportation system of that era. Ferries linked America's growing tidal cities to their surroundings, utilizing an expanding network of toll roads, pikes, and longer-range boats connected to them, enabling efficient if sometimes unpredictable transit from the mid-Atlantic to distant locations like New York and Baltimore.

North of Philadelphia, major ferry operations connected Mercer County, New Jersey, and Bucks County, Pennsylvania. Between 1675 and the start of the American Revolution, Trenton established the Lower, Middle, and Upper Ferry crossings over the Delaware River. The Middle Ferry was linked with a stagecoach line to New Brunswick and provided downriver service to Philadelphia.

|

| River Ferries |

Simple Designs

Some ferries were simply small longboats that were rowed or sailed across a body of water. However, most were purpose-built with a simple design. They essentially consisted of a rectangular platform with a flat bottom and vertical sides. These ferries were easy and inexpensive to construct, with the only requirement being that they could float. The bottoms at each end angled upward, reducing water resistance and allowing for easier movement across the water.

Most upriver ferries lacked landing docks, instead loading and unloading directly onto a natural riverbank, which was sometimes modified to include a sloping earth ramp for entry and exit. In more advanced ferries, a movable ramp was attached at each end, pivoting on hinges and operated by a long pole.

When crossing, both ramps were kept in a raised position. The simplest and most reliable way to move a ferry across a typically shallow river was by manpower, specifically by poling. This method was used by most riverboats and was the technique employed by the Durham boats during the military transport across the Delaware in 1776. Some ferries used oars or winches pulling on ropes.

|

| Photo of 19the century ferry - simple design little changed from 18th century this one powered by winch and rope |

The Ferry to Freedom

The ferry played a major role in the American War for Independence. The movement of supplies relied on them. But most important was the ferry's role in the movement of armies. Some engagements, such as Stonos Ferry in South Carolina (1779), took place at or near ferries, and many others were facilitated by ferry travel.

The ferry played a major role in the American War for Independence. The movement of supplies relied on them. But most important was the ferry's role in the movement of armies. Some engagements, such as Stonos Ferry in South Carolina (1779), took place at or near ferries, and many others were facilitated by ferry travel.The battles around New York in 1776 (the setting for my first novel, The Patriot Spy) relied on ferry crossings to move troops and supplies. Brooklyn was central to Washington's escape from Long Island despite overwhelming British forces. He used the Brooklyn ferry point as his landing spot.

Most famously, the ferries between Pennsylvania and New Jersey played key roles in the American Revolution. As the war moved across the Jerseys, other ferries operated on the Delaware. Trenton’s Lower Ferry earned the nickname "the Continental Ferry” because its owner, Elijah Bond, offered reduced rates to active American soldiers.

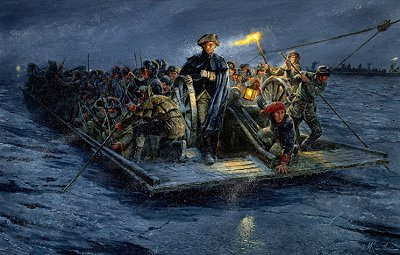

During the British occupation of Philadelphia (September 1777–June 1778), American spies disguised as farmers used ferries on the Schuylkill River, including Gray’s Ferry, to slip in and out of the city. The most famous ferry incident of the war was George Washington and his army crossing the Delaware on Christmas night in 1776, at McConkey’s Ferry. This brave event and related stories are told in my second novel, The Cavalier Spy. But a lesser-known ferry in the region also played a crucial role in the fight for independence.

|

| Washington's Crossing of Delaware on Durham boats in December 1776 |

A Lesser Known Ferry

Some ten miles upriver on the Delaware was an important ferry run by John Coryell, a tavern keeper and ferry operator. Coryell's Ferry crossed the Delaware between what are now Lambertville, New Jersey, and New Hope, Pennsylvania. At the time, both towns were also known as Coryell's Ferry. Though less famous than McConkey's Ferry, Coryell's Ferry was a key crossing during the Revolutionary War.

In early December 1776, Coryell refused passage to British soldiers as General Charles Cornwallis pursued the Continental Army into Pennsylvania. There was also military activity around Coryell's Ferry during this period, with Cornwallis's troops pressing the retreating Americans and guarding against local militias. In 1777, part of Washington's army camped near the ferry, using it to cross into Pennsylvania ahead of the Brandywine campaign.

|

| Coryell's Ferry 1776 |

Mentioned in the Dispatches

Coryell's Ferry is referenced in three of George Washington's papers from December 1776: “General Orders, 12 December 1776,” “From George Washington to John Hancock, 12 December 1776,” “General Orders, 29 December 1776.” Spelling was inconsistent in 1700s America, and the ferry's name is spelled differently in each document—"Corells," "Corriels," and "Coryells."

Campaign of 1778

Coryell's Ferry played a significant role in the Monmouth campaign of June 1778, when the Continental Army crossed there to pursue the British into the Jerseys. The events that initiated that crossing began the previous fall. The British army occupied the American capital, Philadelphia, from September 26, 1777, until June 18, 1778. This occupation compelled Congress to relocate to York, Pennsylvania, which demoralized many Americans.

During that same winter of 1777, General George Washington positioned his army about twenty miles from Philadelphia at Valley Forge, which served as an excellent location for "winter quarters." The forge offered solid ground for defending against British attacks and was a strategic vantage point for observing or blocking British movements.

In early 1778, the British recalled General William Howe and appointed his second-in-command, Sir Henry Clinton, as the new commander-in-chief. Recognizing his vulnerability and aiming to consolidate his forces for a new British strategy, Clinton decided to retreat to New York. His forces set out on June 18, 1777, crossing the Delaware River at Cooper's Ferry into New Jersey. From there, they began a northeast march across the Jerseys.

|

| There were numerous ferries along the coastal and inland rivers of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania |

By then, Washington had the Continental Army on the move. Learning of the British evacuation of Philadelphia, Washington decided it was time to leave Valley Forge.

On June 20, the columns of dust-covered but eager soldiers arrived at the Pennsylvania side of Coryell's Ferry. The next day, Washington crossed to the New Jersey side (at today's Lambertville) and set up his headquarters at the Holcombe House. The main body of the army soon followed the commander-in-chief into New Jersey. This was not a secret, nighttime crossing like at Brooklyn or McConkey's. With a much larger force, including 700 horses and 200 wagons, the 1778 crossing was a large, loud event.

By the morning of June 21, they began pursuing the retreating British. From Coryell’s Ferry, the army traveled through what is now West Amwell (then called simply Amwell). The main body camped near Ringoes on June 22. This effort culminated on June 28, when they fought the British near Monmouth Courthouse in the famous battle of that name. Although it was a draw, the Continental Army faced the British on equal terms in open battle.

|

| Crossing at Coryell's Ferry led to the battle at Monmouth |

A Call for Help

Although Monmouth's maneuver and actions occurred in June, Washington had done extensive prior planning and clearly saw Coryell and his ferry as vital to his efforts to prevent the British from using it and to ensure its availability for the Continental Army. The dispatches to and from Coryell shown below provide insight into the logistical aspect of Washington's war, which required early preparation of the operational area. (Note: indifferent spelling was common across all classes during the time of the Yankee Doodle Spies.)

To John Coryell

Head Quarters Valley Forge 1st March 1778

Sir

I am very anxious to have all the continental flat Boats below Trenton carried up the River as far as Easton or near it, that they may be intirely out of the Enemy’s reach—I have desired the Gentlemen of the Navy Board to order Commodore Hazelwood to collect all those and carry them up as far as Trenton and when he has got them there to let you know it. I shall therefore be exceedingly obliged to you if you will collect a proper number of hands who are used to carry Boats thro’ the Falls and go down for them when you have notice. Or if you do not receive such notice in a few days, the Men may as well go down to Bordentown where the Boats are and bring them up from thence. There are a number of Cannon and some Stores there which I want carried to a place of safety. If you think the Boats can be taken thro’ the falls with the Cannon in them, it will save much expence and secure them perfectly. You are to apply to Messrs Hopkinson and Wharton of the Continental Navy Board at Bordentown for the Cannon if they can be carried up in the Boats.

I see by a letter of yours to Colo. Lutterloh that you want Money for these purposes. You may hire the Men for doing this service upon an assurance of their being paid the moment it is performed. And you will therefore make out the account when you have finished and apply directly to me for the Money when it shall be paid with thanks.

I am &c.

(Washington)

|

| Coryell's Landing Toll House |

Response to His Excellency

Coryells Ferry [Delaware River]

March the 6th 1778

Honoured Sr

I Recd yours of the 1st instant the third at night & am Determined to serve you according to your Directions If Possable the Badness of the weather has hindered me to proceed on with any more Boats since my Last1 but Expect to Start the Remainder in two or three Days that I now have at my Ferry & when they are gone I will go after the Rest I am afraid I cant Bring up any Cannon in the Fleet Boats If there should be any Dur[ha]m boats below as I Expect there is I kno I Can Bring up Canno[n] in them and Will I have ingaged a number of Brave watermen for the purpose & I am dr Sr your Humble sert

Jno. Coryell

P.S. there was a number of peac eis of Duck Left at my place I had to press sleds to move them to Reading & I Kept one for the use of my self & men; If it Cant be spared it is not Cut I will send it on.

J.C.

|

| Coryell's Landing today |