A Bad Rap

This profile is genuinely one of THE badasses of the American Revolution, a struggle that had more than its fair share of tough characters. But John Graves Simcoe wasn't your typical badass, driven by testosterone and a thirst for blood – even though the (very excellent) TV series TURN might make you think he was that and more – a psychopath comes to mind.

Simcoe, as played by actor Samuel Roukin

But the real John Graves Simcoe was quite different. He was, in fact, a well-educated professional officer, liked by his troops and superiors, and respected, and sometimes feared, by his enemies. Born in Cotterstock, England, on February 25, 1752, he was the son of a Royal Navy officer who received a classical education at Eton and Oxford. However, in 1771, Simcoe left school at 19 and bought an ensign’s commission with the 35th Regiment. His education gave him an advantage over most of his peers, as he had a thorough knowledge of classical Greek and Roman military writings. He soon had the chance to apply his knowledge in the dark woods and green fields of America.

Simcoe took a commission at 19Off to America

Simcoe was delayed in sailing to America and arrived after his 35th Regiment had been decimated at Breed’s Hill. During the subsequent American siege, he purchased a captaincy in the grenadier company of the 40th Regiment, where he fought in several battles in New York and New Jersey. Ambitious, he had sought command of the Queen's Rangers as early as the summer of 1776, when the army was on Staten Island. However, it was not offered to him.

BrandywineNew Kind of Unit

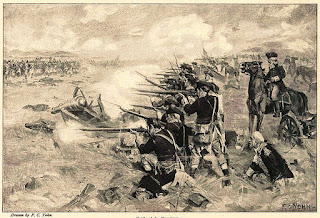

He must have impressed his commander-in-chief, Lieutenant General William Howe, who promoted him to major in October and gave him command of the Queen’s Rangers. The Rangers were once a legendary unit formed by the even more legendary hero of the French and Indian War, Major Robert Rogers. The unit’s reputation had faded along with Rogers, who had left the army. Simcoe quickly began training it in the unorthodox tactics needed for the American war. Clad in green uniforms and rigorously drilled to fight as skirmishers in deep woods, patrol dense forests, and carry out raids and ambushes, they would eventually instill fear in all they encountered. He eventually expanded the unit to about 11 companies, each with roughly 30 men. One was a “hussar” (light cavalry) company. He also added a light infantry and a grenadier company.

Queens Rangers were trained for strength and skirmishingNew Kind of Action

With the arrival of the spring campaign in March 1778, Simcoe’s new unit saw its first action. The Queen’s Rangers engaged two American militia detachments at Quinton’s and Hancock’s bridges in New Jersey. The Americans were defeated by the aggressive tactics of Simcoe and his men. A few months later, the rangers handed a heavy defeat to General John Lacey’s forces at Crooked Billet, Pennsylvania, on May 1. An attempt to trap a reconnaissance detachment led by the Marquis de Lafayette at the end of May was less successful. But things were changing in the middle Atlantic. The new commander in chief, Sir Henry Clinton, was ordered to abandon the American capital, Philadelphia, and march his army to the safety of New York City. With the replenished and newly trained Continental Army nearby in Pennsylvania, Clinton knew the move carried risks. Therefore, he asked Simcoe to help cover the force.

The Queen's Rangers were in their element and performed well at their task, covering the withdrawal through the hot, humid fields and woods of New Jersey. In June 1778, Simcoe received word of his promotion to Lieutenant Colonel, a rapid rise for a British officer and a sign of more to come. The year 1779 saw Simcoe, the Queen’s Rangers, and the kind of warfare they were made for, come to the forefront. A series of small actions and skirmishes occurred throughout the New York region, mainly along the North (Hudson) River. On August 31, 1778, he led a massacre of forty members of the Stockbridge Militia, Indians allied with the Continental Army, in what is now the Bronx. His men were known to burn houses, barns, and stores—actions not unfamiliar to American units in a war that had become one of fire and smoke.

Simcoe employed his rangers aggressivelyIn June 1779, his rangers successfully led the capture of Stony Point and Verplank’s Point on the North River. Simcoe’s men soon joined Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion in a successful raid against rebels at Pound Ridge, New Jersey. With two of the top three British leaders in command, it was difficult for the defenders. A series of small actions followed, including raids, ambushes, skirmishes, and patrols. During one raid on October 17, 1779, Simcoe was ambushed and captured by the New Jersey militia. He was briefly imprisoned and eventually exchanged on December 31. The Queen’s Ranger returned just as General Clinton’s amphibious expedition against South Carolina was beginning.

Rangers go South

In the spring of 1780, Simcoe sailed south to support the British siege of Charleston. After a brief siege, the city surrendered in May. In what may have been a costly mistake, Simcoe was sent back north with Clinton and was soon dispatched to assist Hessian General von Knyphausen in conducting large-scale operations in the Jerseys. His skills and his rangers would likely have been more effective in helping to subdue the South, as would Clinton’s presence. Instead, after a promising start, the southern strategy began to fall apart in the kind of warfare that required Simcoe and his men.

Traitor’s Partner

In an odd twist (sic), in December 1780, Simcoe was assigned to support traitor-in-chief British General Benedict Arnold’s heavily destructive raid through Virginia. He was partly placed at Arnold’s side to keep a close watch on him. However, the two skilled leaders and co-badasses actually got along well. Brigaded with Hessian Jaegers under Major Johann Ewald, Simcoe’s command defeated the unfortunate Virginia militia in several bold attacks around Richmond. At a place called Point of Forks, Simcoe tricked former General Wilhelm von Steuben and seized a stash of valuable supplies.

Climax in the Old Dominion

As luck would have it, Simcoe was in the right place but at the wrong time. Britain’s eight-year effort to hold onto the 13 colonies would, for all practical purposes, end in the Old Dominion. Frustrated at every turn in the Carolinas, British General Charles Cornwallis marched his worn-out and exhausted army north into Virginia. There, Simcoe and his Queen’s Rangers joined him as part of the vanguard. Although battle-hardened, the rangers, like many other British units, found the rebels closing the gap. Things were clearly “going south.” One example is the engagement at Spencer’s Ordinary on June 26, 1781. In an unlikely turn of events, the Queen's Rangers were fiercely engaged by Pennsylvania riflemen under Colonel Richard Butler — the very enemies they were created to defeat. The rangers abandoned the field and their wounded, then hurriedly marched to Yorktown and the main army.

When they arrived at Yorktown, Cornwallis sent them across the York River to secure Gloucester Point. During the summer, the rangers were on a quiet front. This worked well for Simcoe, who had suffered several bouts of illness during the war, worsened by his wounds. His health was deteriorating.

While ill with a fever, the French blockaded the York River. A week later, the French Admiral Comte de Grasse defeated Simcoe's godfather, Admiral Thomas Graves, and the British fleet in the Chesapeake. Cornwallis's army was trapped. In September, the American-French army arrived at Yorktown. Not long after, about 1,000 French troops cut off Gloucester Point. The siege was underway.

But Simcoe was too ill to be of service, and his rangers fell under Tarleton’s command. Simcoe was not expected to survive. Still, in mid-October, he asked for permission to escape with his men on boats to Maryland and fight his way through to New York. He worried that many of his men, being deserters, would be hanged if captured. But Cornwallis insisted that the entire army share its fate. Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe did not die but suffered the shame of surrender at Yorktown on 17 October 1781. He was soon paroled and sailed to New York with his unit. The Queen’s Rangers eventually went to New Brunswick, Canada, and disbanded in October 1783.

Convalescent and Cupid

In 1782, the still ailing Simcoe returned home to Devon, England, to convalesce. There, he met and married Elizabeth Posthuma Gwillim, a wealthy heiress. Her adopted mother, Margaret, had married Admiral Samuel Graves, Simcoe's godfather. So it was a family affair. They had four daughters and a son. By all accounts, he was a devoted family man. Venus, it turns out, was better to him than Mars.

Author, Author

It is beyond this blog’s scope to detail Simcoe’s post-war life in England. He briefly entered Parliament and offered to raise a ranger unit to fight the French. Simcoe wrote a book about his experiences with the Rangers, titled "A Journal of the Operations of the Queen's Rangers," covering the period from late 1777 to the end of the American War. He self-published it in 1787 for his friends.

Lieutenant Governor

Simcoe returned to North America after resigning from Parliament in 1792 to accept the position of Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada (today’s Ontario) under Governor-General Guy Carleton. His resilient personality, well-suited for conflict, often put him at odds with London. However, Simcoe proved to be a highly effective and visionary leader. His ideas were considered progressive for his time. While he valued and supported British institutions, he also advocated for American-style economics and self-reliance. He supported agriculture, property rights, and settlement of what was then the Canadian frontier. He also built roads.

He was fair with the Indians, supported the loyalists, and promoted education and culture. He was anti-slavery even when slavery was still widespread in the British Empire. Fearing a war with America, he moved the capital from Newark to York on the north shore of Lake Ontario—today's Toronto. To help defend Upper Canada from possible American attacks or invasion, Simcoe created a Canadian version of the Queen's Rangers, with himself as its colonel. However, illness struck again. In 1796, neuralgia and gout forced him to take a leave of absence to England. Simcoe resigned from his position in 1798 and never returned to Canada.

War with France

By 1797, war with France resumed, and Simcoe was appointed governor of Santo Domingo. He faced a slave revolt supported by French Republicans and Spaniards. Simcoe was also promoted to Lieutenant General, the highest rank in the army at that time. Illness again shortened his tenure. He returned to England to prepare Plymouth’s defenses against a possible French invasion. Although Simcoe accepted command of the Western District, he did not receive another active field command from the Pitt government. When Britain assembled a coalition against Napoleon in 1806, General Simcoe traveled to Portugal as part of a military mission. However, his old illnesses struck again, forcing him to return home, where he learned of his appointment as commander in chief of British forces in India.

Lost Opportunity

India was arguably the most prestigious and challenging overseas appointment for any British military officer or administrator. And Simcoe excelled at both. There is no telling how the future of the subcontinent might have turned out with him in charge. But it was not to be. He succumbed to his illness on October 26, 1806, in Devonshire. Lieutenant General John Graves Simcoe was only 54. Simcoe was not the crazy character often shown on television. Quite the opposite, Simcoe proved himself to be a learned and scholarly warrior and a forceful leader of partisan forces, among the best serving in the Revolutionary War. He was also a sincere man of peace who helped make Canada one of the best-governed provinces, and nations, on earth. And he might have done the same for India.