Glacial Expanse

Although much of North America was heavily forested in the 18th century, the expansive region of mountain woodlands stretching from New England to the Great Lakes along the northern part of New York made travel slow, difficult, and often dangerous. For centuries, however, the native tribes of the area, including the Iroquois, Abenaki, and Huron, moved through it with relative ease. Passes of knowledge passed down through generations of the tribes turned even the smallest crack in the woods, footpath, or deer trail into their main routes.

However, modern (18th-century) travelers like explorers, hunters, trappers, and armies needed a better way to navigate the often overwhelming wilderness. To do this, they also looked to nature. In this case, the excellent network of waterways was created by glaciers that receded at the end of the last great ice age.

Waterways of War

The resulting waterway extended, with minimal interruption, from the Saint Lawrence River to Lower New York Harbor and the Atlantic Ocean. This narration will focus on the northernmost waters of Lake Champlain and Lake George. Several forts built to defend the waterways played a significant role in the many clashes between the French, Indians, and the British in the 18th century.

Crown Point

This is the story of two forts as Britain and France clashed to control Lake Champlain, the largest body of water south of the Great Lakes and west of the Atlantic Ocean. Like an opposing left thumb, a small peninsula extending into the lake from Champlain's western shore dominates the approach from either side. As the first "battlespace" between Canada and the colonies, it played a crucial role in the many 18th-century conflicts over a North American Empire.

The French were the first to recognize the strategic importance of the location. In 1734, they started building a base called Fort St. Frederic, which they used to launch raids against British settlers in central New York and New England (the hated Bostonnais). During the French and Indian War, the British aimed to neutralize the base and eventually succeeded in capturing it in 1759. They quickly constructed new defensive structures on the site, which they named "His Majesty's Fort of Crown Point." The new fortifications at Crown Point covered more than seven acres, making it one of the largest in North America.

Between the French and Indian War and the start of the American Revolution, Crown Point (like all other spots along the waterway) became less important and was basically put on hold. However, in 1775, the Americans saw the value in capturing the unmanned cannons and weapons for the new Continental Army. It served as a base for American forces invading Canada in 1775 and defending New York in 1776. Crown Point returned to British control when General John Burgoyne launched his 1777 campaign to split up the colonies. It stayed under British control even after Burgoyne surrendered in October of that year.

Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ti is the big daddy of forts, the big kahuna, the Gibraltar of the North, and plays a major role in my novel, The North Spy. The name "Ticonderoga" comes from the Iroquois word tekontaró:ken, meaning "it is at the junction of two waterways." Situated between Lake Champlain and Lake George, the site controlled the transit route between Canada and the American colonies, making it one of the most strategic locations in North America. I visited once when I was very young and twice as an adult and have not even begun to explore its full historical and geographic significance.

French Carillon

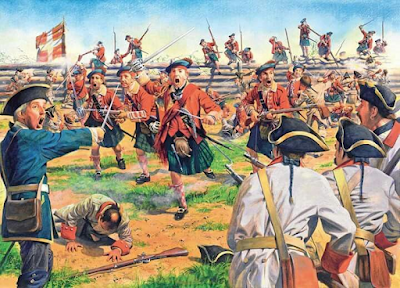

Recognizing its strategic importance, the French first fortified the site in 1755 and named it Fort Carillon. It would play a key role in the upcoming campaigns of the French and Indian War. The strength of the location was demonstrated in 1758 when 4,000 French troops defeated 16,000 British soldiers in a fierce battle called The Battle of Carillon. However, all forts are meant to be taken, and in 1759, the British returned. This time, they drove out the small French garrison.

Rebel Pickings

At the start of the Revolutionary War, local leaders recognized the importance of the fort and its weapons. In 1775, the American siege of Boston surrounded the British but lacked the necessary guns to carry out a proper siege and the gunpowder to risk a full-scale attack.

On May 10, 1775, Colonel Benedict Arnold and Ethan Allen led a surprise attack with a group of Green Mountain Boys and other local militia, catching the garrison off guard and capturing it. General George Washington, the new commander-in-chief of the Continental Army, sent Colonel Henry Knox to Ticonderoga to move the heavy cannons and powder back to Boston. When these captured guns were installed in the battery overlooking the city in March 1776, General William Howe ordered the evacuation of Boston.

Red Deluge

During the summer campaign of 1777 led by British General John Burgoyne, Ticonderoga was a focal point. The large fort was crucial to Burgoyne's plans, serving as his logistics hub and starting point for his final push to Albany and a connection with General Henry Clinton's army in New York City.

Without a Shot

The Americans acknowledged the threat and the importance of defending the fort, but the defenses had been neglected, and the garrison lacked enough troops, munitions, and supplies. Ironically, large fortresses use a lot of resources and are vulnerable if not fully staffed. This was the situation facing the new American commander of the garrison, General Arthur St. Clair. Ticonderoga was surrounded by mountains that, if taken, would put the fort and garrison in danger. St. Clair did not secure those hills, but the resourceful British did – dragging a gun battery to the top of Mount Defiance. Recognizing the danger, St. Clair ordered a night withdrawal, leaving the Gibraltar of the North without firing a shot.

Fort Ann

Nestled in the rugged woods east of Lake George's southern tip, Fort Ann sits at the edge of the rough terrain and marks the start of the lowland routes to Fort Edward and the Upper Hudson Valley.

French and Indian War

Recognizing its strategic position, the British built a small fort there in 1757. It was in 1758 that renowned French and Indian War leaders Israel Putnam and Robert Rogers led a force of 500 men to scout and screen the French at Fort Ticonderoga. On their return, they were ambushed, and Israel Putnam was wounded and captured.

Revolutionary War

Following the fall of Fort Ticonderoga in the summer of 1777, British General John Burgoyne forced the Continental troops to retreat. They pursued them through the dense, rugged woods east of the lakes. The Americans conducted a fighting withdrawal by felling trees and setting up ambush points, then regrouped in a defensive perimeter near the last stronghold before the pass leading to the lowlands – Fort Ann. The British advance guard was on the move, determined to capture the fort.

Impromptu Battlefield

The Battle of Fort Ann took place here on July 9, 1777. This was another delaying action, one of many large and small, that marked the middle phase of the Saratoga Campaign.

The British advance guard, consisting of around 200 men, was confronted at the gorge about a mile north of Fort Ann by Colonel Pierce Long's rear guard, which included 150 men reinforced by 400 New York militia under Colonel Henry van Rensselaer. Long and van Rensselaer launched an attack in two columns when the British paused to wait for reinforcements. One column swung east, threatening the British flank and rear, while the other pushed into the defile.

Gunpowder and War Whoops

The British withdrew to higher ground, and after two hours of intense fighting, the Americans broke contact due to a lack of ammunition and the sound of approaching British reinforcements. However, those reinforcements turned out to be a ruse—a single British officer imitating Iroquois war whoops. While a British victory, the action at Fort Ann delayed the progress of the British Saratoga Campaign.

While the Patriots successfully outnumbered and surrounded the British, they ultimately retreated to Fort Ann and then to Fort Edward after being deceived into thinking that enemy reinforcements were about to encircle them. Nevertheless, the Patriots effectively delayed British movements toward Saratoga and secured an American victory there.

Fort Edward

A series of forts was built at the "Great Carrying Place," a portage around the falls on the Hudson once used by local Indians before colonial times. Located on the "Great War Path," which was later used by the Iroquois and other tribes, both French and English colonists saw its importance and used it during many wars in the eighteenth century.

A French and Indian Fort

During the French and Indian War, General Phineas Lyman built Fort Lyman here in 1755. Sir William Johnson, the British Superintendent for Indian Affairs, renamed it Fort Edward in 1756 to honor Prince Edward, the younger brother of the future King George III. After Fort William Henry was captured by the French, the well-known Major Robert Rogers used it as a base for his Rangers' operations. In 1759, General Jeffrey Amherst's army gathered at Fort Edward for their attack on Fort Carillon and Fort St. Frederic. After the British took the forts, Fort Edward was greatly reduced as the war moved north.

Revolutionary Days

Fort Edward was destroyed by the rebels shortly after the Revolutionary War started. Although it was never used as a defensive structure, its strategic location made it a base for many military officers passing through. The commander of the Continental Army's Northern Department, General Philip Schuyler, used it as his headquarters until the British forced him south on their way to Saratoga in the summer of 1777.

Place of Infamy

The most infamous event of the 1777 Saratoga campaign, the case of Jane McCrae, happened near the fort. Jane, the fiancée (or lover) of a Loyalist officer, was captured by an Indian war party while visiting a house close to the fort. Her fiancée sent another Indian war party to negotiate for her release. When it became clear that the fiancée's envoy would not pay a ransom, her captor, a Huron named Wyandott Panther, became enraged. During the argument, he allegedly shot her. Jane's bloody scalp was brought to the British camp, where her fiancée identified it by its bright red hair. The rest of her remains were buried near the fort.

Patriotic Outrage

The Americans exploited the incident to stir up deep-rooted colonial fear and hatred of the Indians. Given the long history of conflict between the tribes, especially the Mohawks, this was fairly easy to do. Soon, hesitant farmers and settlers began to rally to the cause in large numbers. By the time General Burgoyne's Army was north of Albany, the angry rebels outnumbered him two to one.