This final post of 2023 features another historical figure from my novel, The Lafayette Circle. Although John Quincy Adams plays a relatively small role in this tale of intrigue and chaos in early 19th-century America, he seeds ideas that made Marquis de Lafayette's 1824-1825 visit more than just a celebration of friendship between two nations.

Apprentice Diplomat

John Quincy Adams was destined to grow up in the shadow of his father, John, an accomplished lawyer, statesman, and politician who helped shape the American Revolution and establish the foundation of the United States, becoming its second chief executive. Young John Quincy was born on July 11, 1767, at the family home in Braintree, Massachusetts, which is present-day Quincy. His intensely patriotic and accomplished parents influenced his early upbringing and provided him with a classical education. The American Revolution unfolded before his eyes as he was among the many people in and around Boston who nervously watched the patriots battle lines of redcoats at Bunker Hill in 1775.

Exchange Student

Three years later, he left his mother to go with his father on a diplomatic mission to Europe, marking the start of his real education. From 1778 to 1779, he studied at a private school in Paris, where he improved his fluency in French, the language of diplomats. After this, he attended the University of Leiden in the Netherlands, where he learned some Dutch.

By 1781, he had become proficient enough in French for his father to secure a position for John Quincy as private secretary to one of America's leading diplomats, Francis Dana, who had been appointed US Envoy to the court of Russia in St. Petersburg. When Dana's mission failed, he returned to Paris, where he served as a secretary to the American Commissioners during their negotiations with the British.

The Law and the Hague

When the Treaty of Paris was signed, he returned to the U.S. to study at Harvard College and then in Newburyport under the guidance of Theophilus Parsons, where he studied law. By 1790, he was a member of the bar in Boston. Adams began private practice but also started writing pamphlets on political doctrine and foreign policy, supporting President George Washington's firm stance on neutrality in foreign affairs. This led to his appointment as U.S. minister to the Netherlands in 1794.

The wars of the French Revolution were raging, and The Hague was a hub of diplomatic intrigue. Adams's dispatches and letters provided the Washington administration (which included his father as Vice President) with valuable information. He held a temporary position in London to help facilitate the 1794 Jay Treaty—a pivotal and controversial foreign policy initiative.

The Diplomat

For his commendable service, in 1796, President Washington appointed him as the US Envoy to Portugal. However, when Dad became the nation's second president, he changed his son's assignment to Prussia. But pleasure before business—Adams married Louisa Catherine Johnson, a diplomat's daughter whom he met in Paris when he was just twelve. She proved to be a charming and capable partner to the rising young diplomat. They married in London before heading to Berlin, where he negotiated a treaty of amity and commerce with the Prussians. But in 1800, politics turned against him with the election of Thomas Jefferson, who recalled Adams from his post.

Political Life

Adams returned to Boston, where state and federal politics became his new arena. By 1802, he was a member of the Massachusetts State Senate, and in 1803, he was elected as a U.S. Senator from Massachusetts. "Battleground" is actually a more accurate description. Adams was as sharp-tongued as his father and did not favor "factions." He voted according to his conscience, which often put him at odds with one party or the other. He grew estranged from his father's Federalist Party, which by then had turned against him.

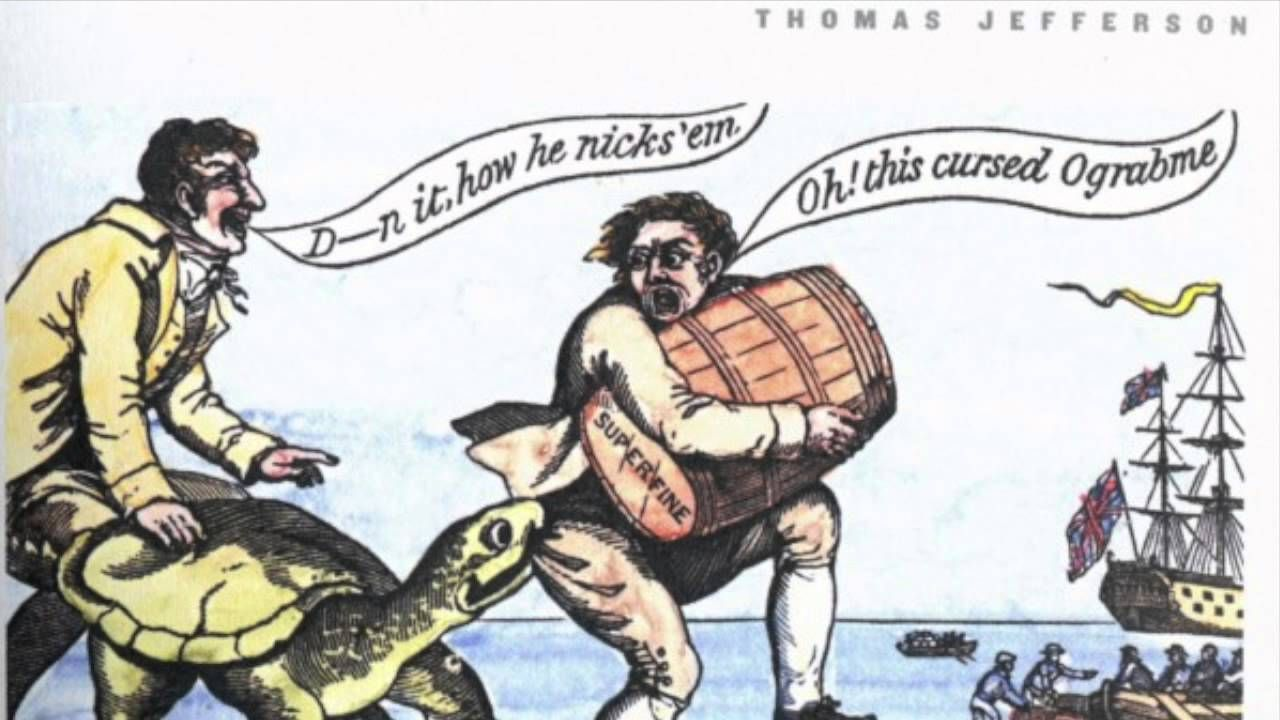

This all reached a boiling point when he supported Thomas Jefferson's Embargo Act, a measure opposed by New Englanders who valued Britain as a trading partner. In 1808, the Massachusetts Senate voted him out of office, which led to his resignation. Adams aligned with the Republicans and took a position as a professor of rhetoric and oratory at Harvard College.

Envoy to Russia

The world was at war with Napoleonic France, and President Madison needed a key player to handle the situation. The highly experienced Adams was the right choice, especially since he had broken away from the Federalists. From that position, the sharp Adams watched the collapse of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte's army in 1812 and the fall of his empire over the next two years. Adams was present at the Court of St. Petersburg just as Czar Alexander rose in stature as a leader in the coalition against Napoleon.

Treaty of Ghent

Meanwhile, war had erupted between the U.S. and Great Britain, which was Russia's ally. Adams eagerly accepted Czar Alexander's offer to mediate in the fall of 1812. The initiative, with Adams as one of the lead commissioners, ultimately failed. However, a follow-up effort in 1814 under Adams's leadership resulted in the Treaty of Ghent. This face-saving status quo ante arrangement changed little diplomatically or politically. Still, it gave the small U.S. the confidence and morale boost of having gone toe-to-toe with what was now the world's reigning superpower.

Like Father, Like Son

After a brief stay in Paris during Napoleon's short return to power in 1815, he followed in his father's footsteps. He traveled to London, where he and Henry Clay negotiated a "Convention to Regulate Commerce and Navigation." Soon afterward, he became the U.S. minister to Great Britain, just as his father had been before him and as his son Charles was to be afterward. His time at the Court of St. James was brief, as Adams returned to the United States in the summer of 1817 to serve as secretary of state in President James Monroe's cabinet. This appointment was mainly based on his diplomatic experience, but also because the president aimed to have a sectionally balanced cabinet during what became known as the Era of Good Feelings.

Manifest Destiny

Adams's tenure as Secretary of State was, as expected, outstanding—especially for someone groomed for the job since the age of fourteen. He worked diligently with Spain to resolve the long-standing dispute over America's western and southwestern borders. The Spanish Minister Onis agreed that Spain would relinquish its claims to lands east of the Mississippi River. In return, Adams decided that the United States would waive its claims to Texas. The two countries agreed on a boundary stretching from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean. Years of dispute were settled through the signing of what was called the Adams-Onis Transcontinental Treaty.

In 1818, he also resolved the northern frontier dispute with Great Britain by establishing the 49th parallel all the way to the Rocky Mountains.

The Monroe Doctrine

Adams was a principal architect of U.S. policy on foreign interference in the Western Hemisphere. This is his main role in my novel, The Lafayette Circle. Instead of a joint U.S.-British declaration to European powers and the Spanish territories in America, he convinced President James Monroe to act independently.

The letter he helped draft to Congress in late 1823 and issued in 1824 served as a firm warning to those hoping to exploit the former colonies, which seemed vulnerable to certain powers. What later became known as The Monroe Doctrine aimed to shield the newly independent lands from recolonization and laid the foundation of U.S. foreign policy for more than a century.

The Second President Adams

The 1824 election was marked by chaos and political maneuvering, all within the boundaries set by the US Constitution. With none of the four candidates—Adams, Andrew Jackson, Henry Clay, and William Crawford—receiving the required number of electoral votes, the election was decided by the House of Representatives, which chose from the top three (Jackson, Adams, Clay) in a one-vote-per-state "play-off." Henry Clay saw Jackson as a dangerous demagogue and supported Adams, effectively helping him secure the presidency. The Jacksonians protested when Adams later appointed Clay as Secretary of State.

Adams worked long and hard as president, but the anger of the Jacksonians (who suspected a corrupt bargain) hovered like a cloud over his term, as they opposed him on everything. Adams's hopes of creating a national university and a national astronomical observatory were crushed. His idea that the western territories should develop gradually was rejected outright. Even his infrastructure plans—building bridges, ports, and roads with federal funding—were blocked. Jackson defeated Adams in the 1828 election.

In an interesting link to my novel, The Lafayette Circle, one of Adams's earliest acts as president was to join General Lafayette on a farewell visit to former President James Monroe at his estate in Leesburg, Virginia.

Representative of the People

In a move that stunned many as "degrading to a former president," Adams ran for a seat in the House of Representatives in 1831, asserting that serving the public as a representative in Congress was not degrading. He represented the people in Congress until he died in 1848. During those years, he fought tirelessly against slavery and its expansion, as well as the various tactics employed by the slave bloc in Congress to expand and uphold their peculiar institution.

Bold Advocate

When Africans arrested aboard the slave ship Amistad were marked to be returned to their owners, John Quincy Adams took up their cause, defending them before the U.S. Supreme Court—and winning their freedom. Adams's entire career had aimed at one main goal—doing the right thing. In this, he faced a mix of success and failure, but his consistent efforts made him one of the top leaders of early America after the founding fathers.