The Place

When General George Washington and the Continental Army arrived in New York in early summer 1776, the strategic situation was grim. British control of the waterways and superiority in artillery meant that New York, especially the island now called Manhattan, could be threatened from any direction. Although the British approach from the sea made a southern attack most likely, the commander in chief had to prepare for assaults from all sides. To his troops' dismay, Washington ordered fortifications to be built all around the island.

The men worked tirelessly with shovels and picks. Despite their efforts, most of these were primitive and poorly constructed earthworks. However, on June 20, 1776, some Pennsylvania battalions of the Continental Army began building a five-bastion fort at the corner of what is now Fort Washington Avenue and 183rd Street.

The quickly assembled earthen-walled structure lacked a water supply and a strong barricade to fend off attackers. Still, it was located on the highest hill on Manhattan Island. This made it an ideal spot for the fort, with views over the Hudson River to the east, the Manhattan valley stretching south to what is now 120th Street, and protection on the north side from high ground that commanded the Kings Bridge approach. They named it Fort Washington to honor their commander-in-chief.

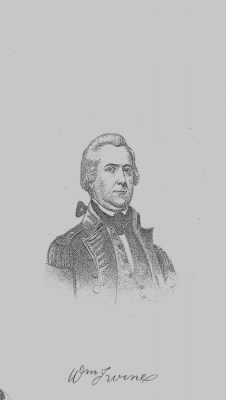

The Namesake

|

| Colonel Robert Magaw hoped to defend the fort |

Washington correctly recognized the high ground at the north end of the island as strategically important. Along with its "sister" fort, Fort Lee (named after Washington's deputy commander, Charles Lee), Fort Washington controlled access to the Hudson Valley, the Bronx, Westchester, and areas bordering New England. It also posed a threat to any forces occupying the central and lower parts of New York Island.

However, without support and with limited troops, Washington's namesake was a liability to his plans and would jeopardize many of his best men. After the British forces led by Lieutenant General William Howe defeated the Continental Army at the Battle of White Plains, they moved to seize Fort Washington, the last American stronghold in Manhattan.

Recognizing this threat, Washington issued a "discretionary" order to General Nathaniel Greene to abandon the fort and evacuate its 3,000-man garrison to New Jersey. Yet, the fort's commander, Pennsylvania Colonel Robert Magaw, refused to abandon it. He believed it could still be defended against the British and begged Greene to let him hold the position.

Greene agreed to leave Magaw in charge until he could consult with Washington, and then crossed the Hudson to review the situation. Sadly, the usually sluggish Howe attacked the fort before Washington could fully assess the situation.

The Battle

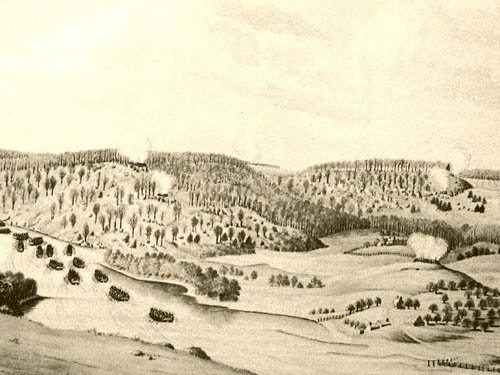

Throughout that summer and fall of 1776, Lord Howe's British land and naval forces carried out an effective, albeit slow, land-sea campaign that pushed the Continentals off Long Island and most of New York Island. By November, the last position the Americans held on Manhattan was around Fort Washington at the northern tip, known as Harlem Heights. Now, with Washington retreating from White Plains and heading into New Jersey, he decided to strike.

Howe planned three attacks: Brigadier Lord Percy was to attack from the south up the island, Brigadier Matthews with the light infantry and Guards was to cross the Harlem River and attack Baxter on the east side, supported by Lord Cornwallis with the grenadiers and the 33rd Foot. The main attack was to target Colonel Rawlings’ position, with Hessian troops commanded by General Von Knyphausen. An additional assault was to be launched on the same side by the 42nd Highland Regiment (the famous Black Watch) under Colonel Sterling.

|

| British ships bombarding |

Early on November 15th, General Howe demanded the fort's surrender. McGaw refused. The British batteries across the Harlem River and the frigate Pearl launched a bombardment against American positions. Percy's forces moved forward to attack. By noon, Matthews landed on Manhattan and began his assault. The American commander defending the works was killed, and his militia retreated to the fort.

However, the main threat originated from the north. General Knyphausen crossed from the Bronx onto Manhattan at Kingsbridge. His two Hessian columns attacked American positions along the high, wooded ground. After fierce fighting, Rawlings’ riflemen withdrew into the fort. Meanwhile, Hugh Percy, leading about 2,000 regulars through McGowan's Pass, attacked Colonel Lambert Cadwallader and his 800 Pennsylvanians on the south side of the fort.

Simultaneously, the 42nd landed on the east side in a diversion and pushed inland behind Cadwallader’s forces. This caused the Americans manning the outer defenses to fall back to the fort as well. With all troops confined inside Fort Washington and under heavy fire, Magaw surrendered to Hessian General Knyphausen. Casualties were high on both sides: the British suffered 450 casualties, including 320 skilled Hessians, while the Americans endured 2,900 casualties, most of whom were prisoners.

|

| The 42nd landing |

Aftermath

From across the river, its sister Fort Lee, George Washington watched helplessly as his last hold on the strategic island of New York evaporated. Almost 3,000 men from some of his best regiments marched off into captivity. As critical, valuable, and irreplaceable supplies and munitions, including 150 cannons, fell to the British, who occupied the fort and renamed it Fort Knyphausen after the Hessian general instrumental in capturing it.

The high ground covering the northern approach to Kingsbridge was turned into a separate fort, named after New York's last Royal Governor, Tryon. A third fort was named Fort George. The fact that the British constructed three forts where a single large American fort once stood is significant. In Magaw's defense, he was not given enough men to properly man and defend the extensive positions.

This is a common theme in fort defenses (to be repeated at Ticonderoga the following year)—they could become a death trap if the garrison wasn't large enough. The British army and its sympathizers then occupied the city until the American victory in 1783. After the war, remnants of the fort disappeared, and the surrounding area became known as Washington Heights. Granite paving marks the former contours of Fort Washington in the southern part of nearby Bennett Park.