The American War for Independence had many fierce fighters, but few senior officers were tougher than the Granite State's own John Stark. Stark was an American made from the same rough cloth as Anthony Wayne and Daniel Morgan, yet also possessed the sharp tactical mind of Benedict Arnold and the strategic vision of Nathanael Greene. Still, John Stark is little known outside his home state of New Hampshire, and even there, he's mostly remembered for his statue in Manchester.

A Rugged American

John Stark, the son of Scottish immigrants, was born on August 28, 1728, in Londonderry, New Hampshire. As a boy, he moved with his family to Derryfield, now called Manchester. It was Stark's home whenever he was not out hunting or fighting.

In the mid-18th century, much of New Hampshire was a frontier of rugged mountains, dense forests, plenty of game—and native tribes. Stark grew up in this wild wilderness, spending much of his time in the forests hunting, trapping, and honing the skills of a backwoodsman. And he was no stranger to the region's violence. These experiences helped shape his rugged individualism and self-confidence, which would later serve him and the nation.

Frontier Hostage

On April 28, 1752, a group of Abenaki warriors captured young Stark while he was out hunting game and trapping fur along the Baker River. One of their members, David Stinson, was killed. Luckily, Stark managed to warn his brother William, who escaped in a canoe. However, the warriors took John and his companion, Amos Eastman, to Canada.

His time as a prisoner toughened him. He and fellow captive Amos were ordered to "run the gauntlet" of braves wielding clubs during their captivity. Few get through the ordeal of the gauntlet without suffering a savage beating, and some succumbed. Stark was not intimidated. Showing the grit he would later be known for, the young man jumped on the first warrior, seized his club, and attacked the astonished braves.

His bravery and strength impressed the Abenakis, and the chief took Stark as a member of their tribe, where he spent the winter. Later, the colony sent representatives to ransom the two captives, with Stark alone costing the treasury 103 Spanish dollars. Stark returned home but now had a strong bond with the clan he had lived with.

Let's Go Rangers!

In 1755, the simmering conflict on the western frontier erupted in North America. The French and Indian War (Seven Years' War in Europe) pulled Stark and his brother William into the fighting. To the British, the war was about building an empire in North America and around the world. For the colonists, it was a fight for survival against relentless enemies.

John william joined Major Robert Rogers's company of rangers. Rogers's Rangers became the most famous frontier fighting force of their time and the inspiration for books and movies. Tough men, accustomed to the hardships of the frontier, the rangers knew and used every trick to venture deep into the forests and cause trouble for the French and their Native American allies.

Young John Stark distinguished himself in the battles at Lake George, Bloody Pond, Halfway Creek, Fort William Henry, the Battle of Snowshoes, as well as the 1758 Battle of Fort Carillon and the 1759 campaign during which Fort Carillon was abandoned.

Crisis of Conscience

In a strange twist, the gritty and hardened Stark faced a unique crisis of conscience in 1759 when British General Jeffery Amherst ordered the rangers to march from Lake George (NY) to the village of St. Francis in Quebec. The town was founded by Jesuit missionaries for converted Indians and was the home of the Abenaki, who had become his foster parents during captivity. Although now a captain and serving as Roger's second in command, the rugged young frontiersman refused to take part in the attack. He soon left the rangers and returned to New Hampshire to spend time with his wife of one year, Molly Page.

Home

When the war ended in 1763, Captain Stark retired and returned home to Derryfield to join Molly and raise a family of eleven children. Unlike most of his peers, young John Stark refused to participate in local politics and declined to attend political meetings, even as the American Revolution approached. However, he overcame his natural aversion to authority when he sensed his country was in peril. In 1774, he joined the local Committee of Safety, which organized the colonies' self-defense and served as the foundation for resistance against British authority. Local safety committees prepared the colonies' towns and counties for political action, self-defense, and war.

Call to Arms

When word of Lexington and Concord reached him, Stark left his farm and sawmill with musket in hand, heading for Boston, where New England was rallying to face the British. Appointed a colonel, Stark was put in charge of the regiment he recruited—tough New Hampshire men. He quickly got into action on 27 May 1775, leading a raid on a British foraging party on Boston harbor's Noodles Island.

Mystic Beach

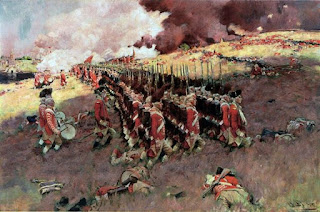

But his real debut came at a place called Bunker (Breed's) Hill on June 17. Stark's regiment was among the first to face the heavy British naval fire to seize the vital ground below the crest. Stark now commanded his own unit plus the Second New Hampshire. On site, Colonel Prescott, the commander, told Stark to decide where he wanted his regiments to defend.

The former ranger quickly saw that the north flank was the weak spot of the American position. There, he placed his men behind a rail fence running from the hill to the Mystic River bank and had them reinforce the rails with straw to fool the British. He also instructed the men to pile boulders along the exposed beach to create a makeshift wall. Then Stark stepped in front of the defenses, marked a spot about eighty paces away, and ordered his men not to fire until the redcoats reached that point.

The sound of the advancing elite Welch Fusiliers at the front of the British army caused men to check their flints as they waited patiently for Stark's command to "aim at their waistbands!" A horrific volley killed ninety fusiliers, causing the rest to panic and flee. The next wave fared no better, as a second volley blasted them. The final British assault was also repelled, ending the attack on the American flank.

Similar results occurred on Bunker Hill itself until a lack of powder forced an American withdrawal, which Starks's men covered with disciplined musket fire. The British took the hill but with the devastating loss of officers and men. Over 1,000 officers and other ranks were killed or wounded. And so, typical of 18th-century warfare, many wounded would eventually succumb.

Passed Over

Sadly, many promotions and appointments, especially early in the war, were driven by politics. When the post-Bunker Hill round of promotions occurred, the Continental Congress passed over Colonel John Stark in favor of less accomplished officers. This would anger Stark and fuel his resentment toward authority.

Continental Line

After the battle, Colonel Stark's command was incorporated into the Continental Army as the 5th New Hampshire Line. The unit distinguished itself while serving with General George Washington's army during the New York and New Jersey campaigns. Stark's men fought fiercely against the enemy in several battles, including Trenton, Assunpink Creek (2nd Trenton), and Princeton.

At Trenton, Washington recognized his bravery and leadership skills in battle, entrusting him with command of the crucial right flank of Nathanael Greene's advance guard.

In the case of Assenpink Creek, he famously led a determined and gritty "forward defense" that stalled the British advance on the main army. Stark's actions at Assenpiunk Creek are vividly portrayed in my novel, The Winter Spy.

But the headstrong and quick to take offense, Stark took issue when the Continental Congress promoted Enoch Poor to brigadier general ahead of him. In March 1777, he resigned from the army in a huff, refusing to obey either man or Congress. But unlike that other famously wronged general, Benedict Arnold, Stark's resentment never turned to treason, only a desire to prove himself.

Stubborn Patriot

While Stark now simmered at his New Hampshire farm, a new threat appeared in the north: a large British invasion force led by Major General John Burgoyne. Conditions in the north were so dire in the summer of 1777 that the New Hampshire authorities urged him to return to active duty in August. He agreed—on the condition that he commanded independently and was not under anyone's control. Then, rallying nearly 2,000 militia, he took the field. However, true to his independent spirit (and stubbornness), he refused a command from the local leader, General Benjamin Lincoln, and kept his men on the east bank of the Hudson River, separate from the main army in New York.

Glory at Bennington

Burgoyne's army was moving south, but his supply lines soon became stretched thin. Hearing about an American supply depot near Bennington, he sent a large force of Germans under the experienced Lieutenant Colonel Friedrich Baum east toward what is now Vermont. When Stark learned of the move, he quickly marched to stop the advance. When Seth Warner's 600 men joined him, the combined forces attacked Baum near Bennington.

Before the main body commenced its attack, Stark stood before his men as he did at Bunker Hill and exhorted them, "There are the red coats, and they are ours or this night Molly Stark sleeps a widow."

The ensuing battle was decisive. The American muskets wore down the exhausted Germans, and soon Stark's men launched an attack, killing 200 and capturing 700 of the Germans. Baum was among those killed. The victorious Americans only suffered 100 casualties but gained a significant psychological and material victory. John Stark's decisive action at Bennington is an exciting part of my upcoming novel in the Yankee Doodle Spies series, The North Spy.

Saratoga Sunset

In September, news of the victory rallied more Americans to the cause – men desperately needed as Burgoyne's final push to Albany clashed with General Horatio Gates's army south of Saratoga, New York. After a second encounter in October, Burgoyne retreated around Saratoga as he debated whether to risk another attack, hold his ground, or retreat along his supply line for the winter. When he finally decided to withdraw, Colonel John Stark had already taken that option away. The Granite General's troops swarmed the woods north of the British forces and cut them off from the safety of Fort Ticonderoga. Burgoyne was forced to surrender, marking a turning point in the struggle.

Getting His Due

In recognition of his distinguished leadership in the campaign that defeated the threat from Canada, Congress finally promoted Colonel John Stark to brigadier general. Congress later awarded him command of the Northern Department, where he twice assisted General John Sullivan during the Rhode Island campaign of 1778. Ironically, Sullivan was a general promoted over Stark earlier in the war.

Brigadier General Stark last distinguished himself in combat in June 1780 against General Wilhelm von Knyphausen's Hessians at Springfield, New Jersey. He commanded two New Hampshire regiments that helped stop one of the advancing enemy columns. As a result, Knyphausen retreated, leaving several hundred casualties. This American victory was the last major battle in the north. The British remained holed up in New York City, content to leave major maneuvers to Lord Cornwallis's southern army.

Although not part of major operations during this period, Stark contributed to the most significant espionage case of the war when he was called to serve on the board of generals for the court-martial of British spy Major John Andre. Andre had gone behind American lines in civilian clothes to meet the traitor Benedict Arnold. While Arnold escaped, Andre was captured while trying to return to British lines. Though Andre was a sympathetic figure, he was nevertheless rightly convicted and received the punishment assigned to spies: death by hanging.

Stark finally left the army in 1783 with the rank of major general. Since George Washington was a lieutenant general (the highest position in the army at the time), Stark had reached the top level of serving Continental officers.

Granite State Citizen

Unlike many of his peers, John Stark did not use his wartime patriotism as a platform for political or economic gain. In 1809, the state of Vermont asked him to travel to Bennington to speak on the 32nd anniversary of the battle. However, Stark was too debilitated from rheumatism to make the trip. Instead, he wrote an eloquent letter praising those who served and everyone who fought, civilian or military, for independence. The old general issued a stern (or perhaps, stark) warning to always stay vigilant in the cause of liberty. The stoic general concluded his letter in a way only he could, injecting some of his fighting spirit with this warning: "Live free or die—Death is not the worst of evils."

Although it should, John Stark's name does not come to mind for most when thinking of Revolutionary War heroes, even in his home state. Interestingly, New Hampshire and Vermont have numerous places named after Molly Paige Stark, while John has only a few monuments. Stark's passionate use of Molly's name before Bennington made her more celebrated than him.

John Stark died, the longest-living Continental Army general of the war, in Manchester, New Hampshire, on May 8, 1822. John Stark was more than a tough fighter—he struck the enemy hard whenever and wherever he could. He lived a life that reflects ideals cherished by all Americans: independence, rugged individualism, and defiance against unjust authority. These ideals remain the Granite General's enduring legacy.

Outstanding Scott! Who knew: My next trip north will make stops in some of the locations you mentioned in the story. Also you answered my question of where the expression “live free or die” came from. Thanks Buddy

ReplyDeleteNick

Nothing gives me more pride as a American than these stories.

ReplyDelete