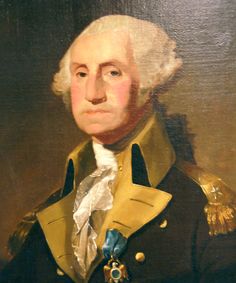

Few Americans (sadly) know much about the eight-year American War for Independence. Likewise, few of the war's units have resonated with the public, other than perhaps the Minutemen, Dan Morgan's Rifle Corps, and maybe "Swamp Fox" Francis Marion's partisans. However, at the time, contemporary writers and some members of the public were aware of the exploits of the Continental Line units. These specially formed regiments, drawn from the states by order of Congress, were the closest thing to regulars Washington had to face the highly professional British and Hessians. I intentionally placed my protagonists in the Yankee Doodle Spies series within one of the most renowned units of the American War for Independence - the Maryland Line. With George Washington's birthday upon us, it is fitting to present the story of one of his favorite units of the war.

The Formation of a Fighting Machine

The 1st Maryland Regiment (Smallwood's Regiment) originated with the authorization of a Maryland Battalion of the Maryland State Troops on the 14th of January 1776. It was organized that spring at Baltimore, Maryland (three companies) and Annapolis, Maryland (six companies) under the command of Colonel William Smallwood. The regiment was established with eight line companies (fight shoulder to shoulder) and one light infantry company (fight like Indians) from the northern and western counties of the colony of Maryland. On 6 July 1776, the Maryland Battalion was assigned to the main Continental Army. On 12 August 1776, it was assigned to Stirling's Brigade and five days later (17 August 1776) adopted into the main Continental Army. The regiment was well-equipped and was one of the few American units to have bayonets, a key factor in its later performance. The regiment was also well trained and disciplined. Arguably the best outfit in the Continental Army at the time.

|

| William Smallwood |

Laurels on Long Island

The Maryland Regiment had joined the Continental Army barely two weeks before the Battle of Long Island. When the British under Cornwallis surprised the Americans by circling around their rear, Stirling ordered all forces, other than the Marylanders, who were outside the fortified position on Brooklyn Heights, to retreat there, leaving behind himself and four companies of the 1st Maryland and Haslett's Delaware Regiment. Stirling led these men against Cornwallis' 2,000 British soldiers who were massed around the Old Stone House, a thick-walled field-stone and brick.

|

| Long Island |

The Marylanders charged the British forces six times to give their comrades time to make their way to safety with the rest of Washington's army in the Heights. Twice, they managed to drive the British from the house, but as more British reinforcements arrived and the Marylanders' casualties mounted, they finally had to give up the assault and try to get to safety themselves. “Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose,” Washington remarked to Israel Putnam as he witnessed the Marylanders repeatedly charge Cortelyou House, effectively holding back the British advance. Later, Washington described their efforts as an "hour more precious to American liberty than any other."

Only Major Mordecai Gist and nine others managed to reach the American lines. Note and spoiler alert - this is a critical scene in The Patriot Spy, where Lieutenant Jeremiah Creed leads some of his men and Gist to safety. Washington witnessing this fighting withdrawal gets Creed assigned to special intelligence missions.

|

| Mordecai Gist |

Back to the story: Of the others, 256 lay dead in front of the Old Stone House, and more than 100 were wounded/and or captured. The dead patriots were buried in a mass grave consisting of six trenches in a farm field. The result of the brief battle was a hard blow for the Americans. More than a thousand men were killed, captured, or missing. Generals Stirling and Sullivan were British prisoners of war. The battalion had lost more than 250 of their number. Most of the Marylanders' casualties occurred in the retreat and desperate covering action at the Cortelyou House. Ultimately, of the original Maryland 400 muster, 96 returned, with only 35 fit for duty. As few troops would stand and fight in the face of England’s battle-tested professional army, the fact that the Maryland Line functioned and operated as a disciplined unit was not lost on Washington.

Apres Brooklyn

After reorganization and reconstitution, the Maryland regiment won more laurels in the desperate actions that followed against numerically superior British forces at White Plains (October 28, 1776), where they faced Colonel Johann Von Rall's Hessians. From 10 December 1776 to January 1777, the regiment was assigned to General Hugh Mercer's Brigade.

|

| Trenton |

During the critical winter "that tried men's souls," the regiment, though much reduced in size, was at the forefront of the fighting at Trenton (December 26, 1776) and Princeton (January 3, 1777). The following year, the re-designated 1st Maryland helped defend Pennsylvania and fought at Brandywine (September 11, 1777) and Germantown (October 4, 1777).

|

| Germantown |

The battle-worn survivors of this regiment ostensibly reorganized in December 1777, continuing their enlistments “for three years or during the war.” But by the close of 1777, few remained from the original line Washington witnessed at Long Island. Bled weak by fighting in the vanguard of the war, they received reinforcements from the Maryland companies of the Flying Camp. They earned recognition for their sacrifices by a nickname bestowed by General Washington himself, "The Old Line."

Moving South

|

| Cowpens |

| Guilford Court House |

A Faded Legacy of Honor

After the war, many members of the Maryland Line continued to maintain relationships formed during the long struggle for independence. In the last days of the war, the Society of the Cincinnati formed chapters in each of the thirteen original states. William Smallwood called for the first assembly of the Maryland Society of the Cincinnati on 20 November 1783 and Smallwood and Mordecai Gist became the first officers of the Maryland chapter of the society, which consisted entirely of officers of the Maryland Line. One of the express purposes of the society was to foster fraternal camaraderie and honor their collective military history. Effectively meeting for reunions as long as there were survivors, the first members of the Cincinnati likely cultivated and propagated the story of the old line. As the revolutionary generation dwindled, perhaps the first “greatest generation” in American history, so faded the memory of gallant service and sacrifice. Unfortunately, this would become the case for the follow-on patriots of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.

|

| Washington was the first National President of The Society of the Cincinnati |