Fans of the fabulous German naval flick Das Boot should not necessarily be disappointed by my little bait-and-switch. As I write this blog, it is the anniversary of the first submarine (sort of) attack in the American Revolution.

Development of a Secret Weapon

| David Bushnell |

The history of weapons development in Connecticut is long. The Nutmeg State has been a center of weapons development from colonial times through modern times. Think Colt, Norden, etc. In the early 1770s, a Yale man named David Bushnell began developing underwater explosives. When the war with Britain erupted, he turned his efforts toward a delivery system. He moved his work to Old Saybrook, Connecticut, where he developed a submersible boat that could attach one of his underwater charges to a ship. Bushnell named his boat the Turtle, although it looked more like a shellfish. The Turtle measured 10 feet by 3 and 6 feet tall. Letting water into a bilge tank lowered the Turtle into the water. It climbed when a hand pump evacuated the water. Crude hand-cranked propellers moved the boat. The Turtle held a crew of one and could operate underwater for thirty minutes at three miles an hour.

| Diagram of the Boat |

In the summer of 1776, the British invaded New York and seized western Long Island (see my highly acclaimed novel, The Patriot Spy), so Bushnell's boat was moved back to Connecticut. The Americans, driven from post to post by superior British soldiers, weapons, and discipline, were even more outmatched by the Royal Navy. Desperate times called for desperate measures.

British landing at Staten Island

The Black Operation

In a secret operation (the term "black op" had not yet been coined), approved by General George Washington, an expedition aboard the Turtle was launched in New York Harbor. An hour before midnight on September 6, Sergeant Ezra Lee began his daunting mission: to navigate the untested Turtle through hazardous waters in an attack on British Admiral Richard Howe's flagship, HMS Eagle. We know Howe from earlier posts. Black Dick was the brother of William Howe, the British commander in chief in North America. Taking out his ship (and possibly him) would be what we today call an asymmetrical attack.

The Turtle takes on the Eagle

The Eagle was moored near Governors Island, just off the southern tip of Manhattan. Yankee rowboats towed the Turtle from the Battery to within striking distance of the British ships at anchor. Lee struggled to navigate for over two hours, and his chances seemed bleak. Then suddenly, the river's tidal currents subsided. Lee, against all odds, reached the Eagle! He tried to fix an explosive charge to the hull, but he failed. The Turtle's boring device struck metal - likely a plate connected to the ship's rudder. Tired and struggling to stay afloat and breathe, the undaunted Sergeant Lee tried once more to pierce the hull. However, he was unable to keep the Turtle beneath the ship.

Treachery

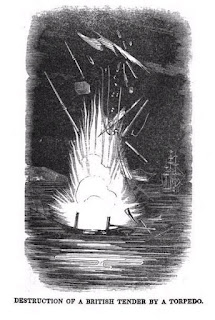

Unknown to Sergeant Lee (or George Washington), a spy had alerted the British to the possibility of an unconventional attack. Expecting subterfuge, alert British soldiers on Governors Island spotted the submarine and rowed out to investigate in the dark waters. Rather than risk capture or an unwanted explosion, Lee cut loose the "torpedo," a specially designed explosive device intended to sink the Eagle. The torpedo floated half-submerged toward the approaching British boat. Fearing the worst, the British turned their longboat around and made straight for Governor's Island. Sergeant Lee, meanwhile, pedaled madly toward the safety of The Battery. Fortunately for the British, the torpedo was caught in the strong currents at the confluence of the North (Hudson) and East rivers and exploded, sending plumes of wood and water high into the dark September sky. But fearful of another such attack, the British ships pulled anchor and moved to the upper bay.

A spy may have alerted the British

Both Ezra Lee and David Bushnell went on to serve in other battles and campaigns. Sergeant Lee served in several pitched battles: Trenton, Brandywine, and Monmouth. Bushnell led several other "mining" operations along the Delaware River and served at Yorktown. His torpedoes wreaked havoc near Philadelphia.

Bushnell also received a medal from the commander in chief after the war. Many "black operations" were only grudgingly recognized by Washington, and all of them were acknowledged after the conflict. His Excellency understood that secrecy must be maintained before, during, and after covert operations. Bushnell moved to Georgia after the war, where he died. After the war, Lee returned to Connecticut. Remarkably, both men lived into the third decade of the next century.

What Gives?

Most of the account of the attack comes from Ezra Lee's report. Of the events of the night of September 7th, 1776, the British logs are strangely silent. They record no rebel attack nor any explosions in the vicinity of the Eagle. So what gives? Did this actually happen? It seems implausible that Lee (along with Bushnell) would concoct a tale of failure...or would he?

Another attack was tried a month later with similarly disappointing results. It is axiomatic that proponents of a program zealously pursue it, sometimes fudging figures or achievements to maintain support. Or did the British keep the attack secret to protect their spy? Would they forgo the obvious propaganda value of exposing a foiled attack? Were they hesitant because they were unsure that future attacks might succeed? Then there is the matter of historiography: some British naval historians assert that the Turtle could not have sustained itself and navigated as the Americans claimed. So they believe it was a hoax. If so, this would not be the last hoax operation in America's military history. Maybe the hoax was on them.

| Another rendition of the Boat |

No comments:

Post a Comment