A House Divided

The American Revolution was as much a civil war as a rebellion. Yes, the colonies rebelled against the king and parliament's laws, but not everyone joined the rebellion. Most who did initially fought to defend their rights as Britons. Many others (some say most) stayed indifferent. Although it lacked grand capitals or palaces like in Europe, America in 1775 was thriving.

The Atlantic coast was a network of small cities and towns, with many well-maintained farms between them. In the south, many (but not all) of these were cash-crop plantations. Trade was expanding, and merchants were making money. People were prosperous and healthier than in Europe, thanks to the economy, a better diet, and less crowded living conditions. In 1775, the American colonies likely had the best standard of living in the world. Many viewed this prosperity as a direct result of America's position in the British empire and saw no reason to risk it all. Then came the taxes to fund the war against the French.

Who are these people?

|

| John Graves Simcoe |

The Loyalists (and initially many patriots) saw themselves primarily as British subjects loyal to their King. Politically, they were Tories. For many, this almost ended any debate about America's status and shifted the focus to how best to preserve certain British liberties. Many Loyalist leaders, like Joseph Galloway of Pennsylvania, passionately pushed for a political solution to the conflicts. They wanted Americans to keep their rights and gain self-rule within the British Empire.

One can only imagine the emotions swirling as their fellow countrymen, Whigs (the patriots), gradually but surely decided on a full split. Imagine that sickening feeling of watching your country, your world, slip away from you. Still, few Loyalists thought the outcome would be anything but the King victorious. That made the ending an even more bitter pill to swallow.

Some pundits have observed that at the start of the war, loyalty was divided roughly 30-30-30: one-third rebel, one-third loyal, and one-third neutral. I believe these figures fluctuated with the changing fortunes of the war and the proximity of the British Army. However, many so-called neutrals, in my view, were not truly neutral. This provides a good starting point, but the situation was more complex. Certain regions, like the Mid-Atlantic, tended to have more Loyalists than areas like New England. The South was more evenly divided, as the brutal fighting there shows. As the war went on and France joined on America's side, Loyalists made up between 15 and 20% of the 2.1 million white inhabitants in the colonies.

Why Remain Loyal?

For the Loyalist, it was all about loyalty. I know, it sounds clichéd, but those who remained loyal throughout the eight-year war were men and women with a worldview that supported an ordered state, the foundation of which was a monarch reinforced by royalty, the nobility, and the upper classes. Loyalists were content with the world they lived in and did not welcome the upheaval caused by rebellion. They looked down on the extremism shown by the patriots.

Local Loyalist Militia

The Loyalists took pride in Britain's superior form of government, characterized by representation in two houses of Parliament and a constitutional monarch as the head of state. They also valued the sense of order that came with the class system. The British had defeated the hated French in the Seven Years' War and in the French and Indian War in America. The "empire" had not yet reached its peak (which would happen around 80 years later), but the King indeed ruled over a growing global empire built on mercantile trade. Trade from which they and all "good Britons" profited. Who could argue? And who would give that up? Who indeed...

What did they Contribute?

The Loyalists were both a blessing and a burden to the British generals leading the war in America. In some ways, they served only as a placebo. British authorities were constantly reassured by key Loyalist figures that most Americans supported the King and were, at worst, neutral, making them easier to win over. As a result, little genuine effort was made to win the hearts and minds of the Americans. In some respects, the idea that loyalty could be coerced was mistaken; this approach assumed the rebellion could be defeated solely through British strength. Loyalists eagerly played their parts, forming regular units similar to the patriot Continental Line and maintaining various local Loyalist militias.

Cowboys Capture a Patriot

In the guerrilla conflicts known as the "Cowboy versus Skinner" fights, the Cowboys were involved. Loyalist spies and sympathizers were omnipresent, ready to inform a British commander about the positions of the hated rebels. Combined with the world's most powerful army and navy, this should have made suppressing the rebellion quick and straightforward. In terms of numbers, Loyalists under arms were substantial. Throughout the war, an average of 10,000 Loyalists served in well-organized and well-equipped "regular" units called Provincials, who were equipped and organized similarly to British regulars but typically wore green jackets. This does not include numerous Loyalist militia groups, which fluctuated in response to the ebb and flow of the conflict.

Loyalist Provincial Infantryman

George Washington would have traded all of Mount Vernon for that number in the Continental Line. According to most accounts, Loyalists of all kinds fought valiantly. Despite lacking as many top-tier leaders as the rebels, they still had some very talented ones, such as Colonel John Graves Simcoe (Queen's Rangers), General Cortland Skinner (New Jersey Volunteers), General Oliver Delancey (Volunteer Corps), and Colonel John Hamilton (North Carolina Volunteers). In certain theaters, especially in the South, Loyalist irregulars were considered even more effective fighters than Loyalist regulars.

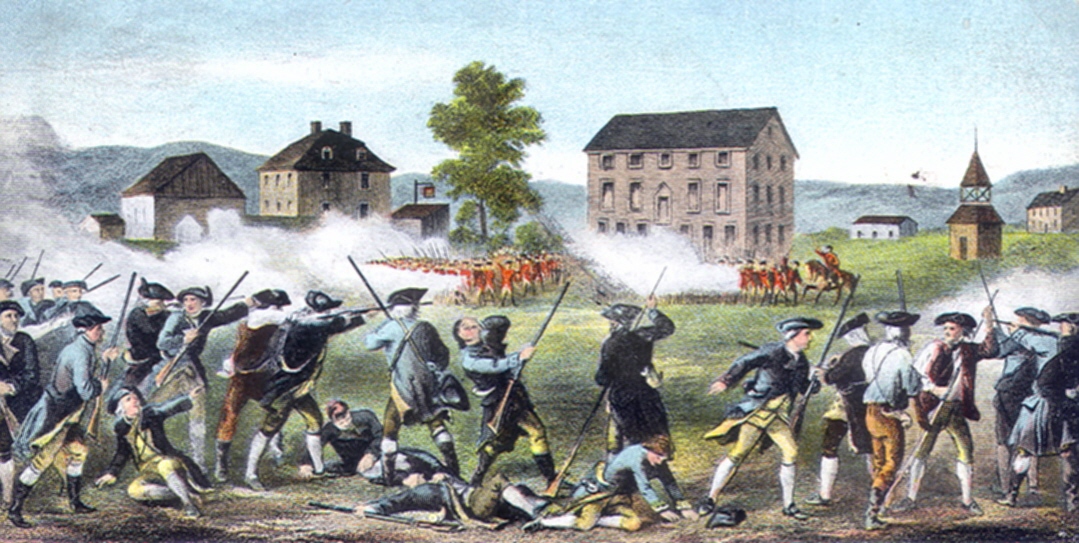

|

Loyalists fought ferociously but vainly in most battles

especially at King's Mountain |

What was their Vision?

Loyalist plans for America's future focused on some form of local representation within the British Empire. In the early days of the political struggles, before open rebellion, that was the overwhelmingly popular view in all the colonies. But after Lexington and Concord, the slippery slope became even more treacherous as the British made mistake after mistake. When the scales tipped toward rebellion, the Loyalists had to improvise both politically and militarily.

Tarleton's American Legion: Loyalists in Action

However, they never had a solid plan or a clear strategy. Why would they need one? They were, after all, Britons. They possessed overwhelming power — the King, his wealth, and his military might. I believe that was ultimately their downfall.

Over-reliance on British authorities, both military and civil, made the Loyalists complacent and even dependent. Since losing to the rebels seemed unthinkable, developing a thorough Loyalist alternative never truly materialized. It certainly wasn't clearly communicated to the public. Conversely, as the war progressed, the British grew increasingly less confident in Loyalist political and military support. By the end of the war, the British saw the Loyalists as a nuisance, and the Loyalists grew resentful of their benefactors.

What was their Fate?

I plan future deep dives into the Loyalist cause but obviously - they lost. They lost big time: land, slaves, homes, families, and pride. With bitter and despondent hearts, some 80,000 or so left the 13 colonies for "British" lands such as Canada, East Florida, the West Indies, and Great Britain itself. Their struggle continued as the now largely impoverished diaspora was treated poorly by its one-time benefactor.

|

Loyalist refugees flee to

Canada (most went by ship) |