The Naval Advantage in 1776

This past week marked the anniversary of the British landing on Long Island and the battle that shares its name. As most readers of this blog know, the invasion and the events that followed set the background for my novel, The Patriot Spy. I thought I’d use this blog to discuss the role of naval power in the campaign. The American Army under General George Washington essentially had no information about British plans after General William Howe withdrew his besieged forces from Boston. However, it wasn’t hard to see that the main British advantage in the war was the Royal Navy.

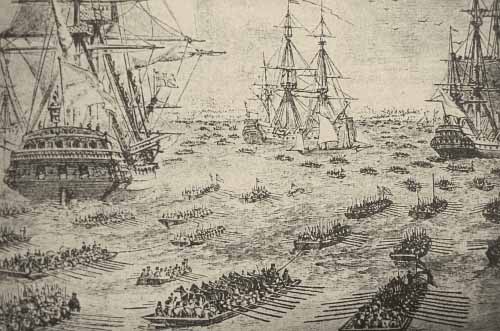

|

| 1776: British fleet at Staten Island |

Early Success, Defeat, and Triumphs

|

| Destruction of the Spanish Armada |

In some ways, the story of Britain is tied to its navy. During the time of the Yankee Doodle Spies, Britain had the greatest navy in the world and, more importantly, had over a century of knowledge and experience in using that advantage effectively. Many are familiar with the victories of the 16th-century English navy under Elizabeth I against the Spanish. However, during the 17th century, England and its navy went through a period of upheaval.

The English Civil War, three wars with the Dutch (who had surpassed Spain as the world's leading mercantile and naval power), and the "Glorious Revolution" all affected the navy's development, both positively and negatively. During that period, the English and Scottish fleets merged but, on paper, remained separate. The Dutch Wars initially favored the Dutch, who achieved remarkable naval victories.

Still, Britain gained the key Dutch colony of New Amsterdam (1664), and it learned how to develop its navy through the experience of defeat. By 1692, the British boasted the finest fleet in the world. The political alliance with the Dutch, which recognized their ruler William of Orange as William III of England, strengthened both navies.

In a curious partnership, the Dutch fleet operated under British admirals in the subsequent wars with France and Spain that dominated the late 17th and most of the 18th century. The British were able to expand their global operations, and through a series of wars, they captured colonial possessions both large and small to support their naval and commercial needs.

.jpg/1024px-Het_verbranden_van_de_Engelse_vloot_voor_Chatham_-_The_Dutch_burn_down_the_English_fleet_before_Chatham_-_June_20_1667_(Peter_van_de_Velde).jpg) |

| Dutch burn the British fleet at Chatham |

Britannia rules the waves!

|

| Royal Navy in Action |

The Royal Navy of 1776 had a confidence rooted in achievement. Part of that success included what would later be called "combined arms" operations—using Royal Marines for small sea-land actions and collaborating with the Royal Army for major campaigns, mainly moving forces and guarding supply routes. This approach was developed during the Seven Years' War (French and Indian War) in North America.

As the rebellion began, the Royal Navy became Britain's greatest advantage over the poorly connected coastal colonies, which were linked by a few poor roads. America depended on the sea, and controlling it was central to any plan to suppress the colonies. Trade could be blocked, starving the colonies that relied heavily on Britain for many finished goods.

Ironically, this policy was among the grievances that sparked the rebellion. Britain's dominance at sea swayed some Loyalists' sympathies or at least their hostility toward the rebellion. To many, it seemed reckless to challenge the world’s strongest naval power—what was then the greatest global naval force ever. These concerns proved valid for most of the war. America had no real navy and was hurriedly building a small one, mostly to boost national pride rather than for strategic advantage.

In reality, America’s naval strength came from privateers—many from merchant ships converted due to British control of the seas—another irony. Effective naval use allowed Howe to escape a tactical trap in Boston. It enabled him to execute a successful sea envelopment and move into New York Harbor, shifting the war’s focus and pace in Britain's favor.

Invasion, they're coming!

|

| British landing at Gravesend on Long Island (near the site of Brooklyn's Verazano Bridge) |

The Royal Navy isolated New York from the sea and made its port useless. The port gave the city its strategic importance, as New York in the 18th century was not the largest city in America. The Royal Navy provided reconnaissance, naval gunfire, and transport for a series of landings at Staten Island, Gravesend, Kips Bay, and Westchester (Throgs Neck, Pelham, etc.).

British naval movements confused the Americans and threatened nearby areas. General Howe had no plans to attack. More importantly, it limited General Washington's ability to move troops and forced him to defend a larger area than he could cover with his soldiers and guns. Surprise, maneuver, and firepower are key multipliers in any conflict, but they are even more effective when you also have overwhelming forces!

As discussed in The Patriot Spy, only extremely unfavorable winds and tides kept the other Howe (Admiral Sir Richard, William's brother, and naval force commander) from surrounding Washington's forces on Long Island, who were tucked into a desperate defensive position on Brooklyn Heights.

If conditions had been right, Howe's fleet could have bombarded Washington from behind and, combined with the army besieging Washington's front, forced surrender in the summer of 1776. Would losing George Washington and a large part of the Continental Army have ended the war then and there in Britain's favor? Well, that's the subject of another blog.

Those landing barges look remarkably like Higgins boats!

ReplyDelete