War in the Shadows

Students involved in insurgencies have long recognized the importance of cutting off the insurgents' external support. Throughout history, few insurgencies or rebellions have succeeded without outside help, which can include moral support, funding, training, weapons, equipment, supplies, political backing, and military aid.

Early in the insurgency that would turn into rebellion after Lexington and Concord, the Americans established a way to keep dialogue and coordination among the colonies and later states. It quickly became clear that America would need to reach across the Atlantic as well. Winning over Americans was only one part of the complex struggle now beginning. Securing support in Britain and forming alliances with sympathetic countrymen would also be vital for gaining recognition for the new nation. Furthermore, the European powers would offer fertile ground for support if properly “tilled.”

A Secret Committee

By the time the Second Continental Congress met in

Philadelphia in 1775, this need for international support resulted in the

formation of the Committee of Secret Correspondence via two resolutions of 29

November:

RESOLVED, That a committee...would be appointed for the

sole purpose of corresponding with our friends in Great Britain, and other

parts of the world, and that they lay their correspondence before Congress when

directed.

RESOLVED, That this Congress will make provision to

defray all such expenses as they may arise by carrying on such correspondence,

and for the payment of such agents as the said Committee may send on this

service.

Because of the secret nature of the work involved, the members soon added the word “Secret” to its name. The committee received significant authority from Congress to carry out multiple functions: public and secret diplomacy, intelligence gathering, and public relations/influencing opinion. In many ways, it functioned as both the State Department and the CIA. It served as the Continental Congress’s eyes and ears in Europe and would soon become its arm in that region.

Extract of Committee's Secret Instructions

First Members

Congress effectively chose the original members of the committee, bringing together notable figures such as Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Harrison, Thomas Johnson, John Dickinson, John Jay, and Robert Morris. Later, additional members joined, including James Lovell, a former schoolmaster, Bunker Hill veteran (arrested by the British for spying), and a Congress member, who developed the committee’s first codes and ciphers. It’s likely that Dr. Benjamin Franklin, who represented the American colonies in dealings with the British government for many years, contributed a wealth of ideas and experience gained abroad. John Jay and probably the others had experience organizing secret meetings and activities on the road to rebellion while surrounded by loyalists eager to expose them.

The Committee at Work

Tactics and Tradecraft

It is a tribute to the American leaders of the era that they were quick to learn and adopt the most sophisticated techniques and practices long used by the great powers of Europe. They employed clandestine agents abroad, conducted covert operations, created codes and ciphers, used propaganda, and carried out covert postal surveillance of both official and private mail. They made use of open-source intelligence by purchasing foreign publications and analyzing them. Most notably, they established an elaborate communication system that used various couriers. Another major innovation was the development of a maritime capability independent of the Continental Navy, designed for smuggling, moving agents, managing correspondence, and intercepting British ships.

First Actions

The committee acted quickly. They started regular communication with English Whigs and Scots who supported the ideas, if not all the actions, of the Americans. The experienced and worldly Benjamin Franklin was the most active, reaching out to a wide range of contacts he had built up in Britain and Europe in a sophisticated effort to gain support for the patriot cause.

Franklin secretly reached out to Spain through Don Gabriel de Bourbon, a member of the Spanish royal family and Franklin's associate. He subtly suggested the benefits an American alliance could bring to Spain.

Agents at Home

But curiously, France was the first to reach out, sending Julien Alexandre Achard de Bonvouloir to Philadelphia to evaluate the possibility of covert aid and political support.

In December 1775, committee members Benjamin Franklin and John Jay attended a secret meeting with the French intelligence agent de Bonvouloir, who was dressed as a Flemish merchant.

Franklin and Jay wanted to know if France would help America and at what cost. They stressed an urgent need for arms and munitions, which would be exchanged for American tobacco, rice, and other crops. De Bonvouloir advised that the French government should avoid any involvement in transactions with the rebels. Instead, private merchants would handle them.

Father of American Counterintelligence - John Jay

Franklin assured de Bonvouloir that America would not reconcile with Britain and that once it declared independence, France should form an alliance. This marked the start of a long-term effort to bring not only French aid but also French arms into the fight.

Agents Abroad

Franklin and Jay were encouraged by French interest in the American cause. In early March 1776, the Secret Committee appointed Connecticut lawyer Silas Deane as a special envoy to negotiate with the French government in Paris. His mission was to secure covert aid and gain political support through Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, Louis XVI’s Foreign Minister. Vergennes skillfully managed both public and secret diplomacy for the French king, handling them with a steady hand.

The committee eventually included an American living in London, Arthur Lee, a member of the well-known Lee family of Virginia. Lee had contact with the French playwright Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, a polymath, playwright, clockmaker, and diplomat who was also a secret French agent. Using a letter sent by the committee, Lee supplied Beaumarchais with information about American successes—much of which served as propaganda to influence French opinion. Interestingly, people today might recognize Beaumarchais not for his dedication to freedom (and making money) but for writing the Figaro plays: Le Barbier de Séville, Le Mariage de Figaro, and La Mère coupable. These later became operatic adaptations that are still enjoyed today.

But Beaumarchais was a supporter of the American cause and did not need exaggerated reports to spark his passion for freedom. While working with Deane in Paris, he influenced French Foreign Minister Charles Gravier, Comte de Vergennes, and King Louis XVI to provide the colonies with secret shipments of gunpowder and war supplies. This assistance was crucial in the early years of what had now become a war. The front company Rodrigue y Hortalez (R&H), registered as a Spanish trading firm, was used for this effort. R&H facilitated the shipment of surplus French arms and munitions to the West Indies, mainly to the Dutch colony Saint Eustatius, where American agricultural products were traded for war supplies.

Deane was responsible for the earliest aid to America’s struggling army through his efforts. Besides organizing secret shipments (with R&H being just one covert operation), he recruited French officers, made introductions, sought ships for privateering, and promoted the American cause among French insiders. Some of the officers he recruited included the Marquis de Lafayette, Baron Johann de Kalb, Thomas Conway, Casimir Pulaski, and Baron von Steuben—a list of notable ex-pat freedom fighters.

The American commissioners in Paris navigated a whirlwind of intrigue as they wooed and charmed the French while fending off Sir William Eden’s British secret service. Eden had sent an American named Paul Wentworth to Paris when Silas Deane arrived. Deane was familiar with Wentworth, and soon he was reporting on Deane’s activities and later, Franklin’s. Wentworth also recruited Edward Bancroft, the secretary of the American Commission.

But Lee was now in Paris, as was Benjamin Franklin himself, who had sailed for France in December 1776. Throughout 1777, the full-court press was in motion. The British and French were secretly opening the American commission's mail through various covert operations. Servants and friends were recruited to spy, influence, and report. Bancroft provided insider information to Wentworth and Eden. And so it went. Meanwhile, Franklin charmed everyone he could, was the toast of Paris, and kept wielding influence. He knew every word and gesture reached Versailles and London, and every step he took reflected that awareness.

What's in a Name?

The Committee of Secret Correspondence became the Committee of Foreign Affairs in April 1777, but kept its intelligence functions. As the first American government agency for both foreign intelligence and diplomatic representation, it basically served as the predecessor to the State Department, the Central Intelligence Agency, and today's Congressional intelligence oversight committees.

Despite the name change, the Foreign Affairs Committee continued to play a key role for Congress, acting as the nation's eyes and ears in Europe. Note: To possibly confuse the British, Congress created a separate "Secret Committee" in 1775 to acquire supplies, which by its nature needed to be kept hidden from British eyes and ships. Many of its members also served on the Committee of Secret Correspondence. It became the Committee of Commerce around the same time its 'sister" committee was renamed the Committee of Foreign Affairs.

The Committee of Foreign Affairs combined

Payoff

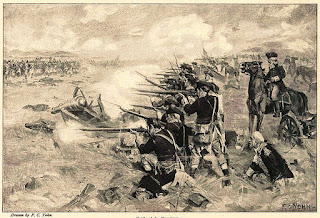

The Committee of Secret Correspondence/Secret/Foreign Affairs Committee’s efforts paid off tremendously when an American army, equipped with arms and munitions secretly supplied by France, forced the surrender of a British army at Saratoga in October 1777. No one in France could recall the last time a British army surrendered to the French. The road to a treaty with France had now become a fast track. However, the committee was not finished. It still had to work out the details of an alliance, future loans to America, and the foundation for negotiations and peace. The capitals of Europe were also a target as the commission aimed to gain support from the Netherlands, Prussia, Spain, and Russia. But those are stories for another time.