Who were these guys?

In the days when American schools taught history with some substance, almost all students learned the word "Hessian" when the American Revolutionary War was discussed. These were the tall, fierce foreigners hired to help crush the rebellion. Tall men who fought us with a cold-bloodedness that even unsettled some British officers and soldiers.

Most of what we learned about the Hessians in school centered around perhaps their lowest point - the battle of Trenton, where a force of over a thousand elite infantry was captured by General George Washington's ragtag, half-starved army. But the Hessians were just some of the Germans King George hired to put down the rebellion. Although they made up the largest group, more than half, since there were German settlers in parts of Pennsylvania, Maryland, and Virginia, it was easy to label all the German mercenaries as the same. That name, which struck fear into the hearts of Americans, became a symbol of their fierce reputation.

Who they were

German soldiers made up about a quarter of the British fighting force in America. That term 'Hessian' refers to all the soldiers fighting in units leased to the King of England by various prince-lings of what was called Germany. Friedrich Wilhelm II, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel, was the most famous among these German princelings, and he had the best mercenary force on the continent.

During the time of the Yankee Doodle Spies, Germany consisted of over 300 independent yet interconnected states, including dukedoms, princedoms, archbishoprics, electorates, margravates, landgraves, and others. These would be significantly consolidated about thirty-five years later by Napoleon. Most of these soldiers came from Hesse-Kassel and Hesse-Hanau, with others recruited from regiments raised in Brunswick, Ansbach-Bayreuth, Waldeck, and Anhalt-Zerbst.

|

| Hessian Grenadiers |

The typical German soldier was conscripted from the lower classes of these regions: men who had no other way to avoid conscription, such as paying a tax, leveraging social status, or bribing a corrupt official. Occasionally, these "dregs" included craftsmen, tradesmen, educated men, and other men of substance, as well as the occasionally fallen cleric. However, most German soldiers who fought in America were farm boys from farms that had fallen on hard times.

Therefore, in most cases, these men were forced into service by circumstances. The fortunate soldier who did not fall in battle or die from disease might reach the rank of corporal or sergeant. But calling the German soldiers mercenaries is a bit misleading. They were soldiers serving in the army of their prince. It was their princes who were mercenaries in leasing out entire regiments and companies to the King of England. This was not uncommon in the 18th century.

|

| Hessian Jaegers zu Fuss und zu Pferde |

Where they served

The first wave of German troops arrived in 1776 to support the British in their planned attack on New York. Their initial engagement was at the Battle of Long Island. Still, the Hessians also fought in many other battles during the Revolutionary War, including Harlem Heights, Fort Washington, White Plains, Savannah, Trenton, Bennington, Bemis Heights, Freeman's Farm, and Guilford Courthouse.

They served as garrison forces and participated in hundreds of smaller skirmishes throughout the colonies. German troops comprised a significant part of Cornwallis's surrendering army at Yorktown. They were known for their ruthlessness, and American propagandists often exploited that reputation to stir up fear, anger, and resentment against them and their British commanders.

|

| Hessians were present at Yorktown's surrender |

How many came

| Jaegers |

The British hired 30,000 German soldiers, and the payment went into the royal coffers of the German princes, not the troops. The units came from the German states of Hesse Cassel, Hesse Hanau, Brunswick, Anspach, Bayreuth, Anhalt Zerbst, and Waldeck.

Place Number sent Number not returned home

Hesse Cassel 16,992 6,500

Hesse Hannau 2,422 981

Brunswick 5,723 3,015

Anspach - Bayreuth 2,553 1,178

Anhalt Zerbst 1,152 168

Waldeck 1,225 720

The total sent was 30,067 from 1776 to 1782; 12,562 did not return... 7,754 died (mostly from disease) and 4,808 remained in America... Perhaps they were the first great wave of non-English speaking immigrants to America.

How they dressed and armed

The Hessian soldiers included infantry and hussars (dismounted), three artillery companies, and four battalions of grenadiers. The infantry were sharpshooters, musketeers, and fusiliers armed with smoothbore muskets. The line companies carried muskets, bayonets, and short swords called hangers. They contrasted with the redcoats by wearing dark blue jackets and tricorne hats. In a style unique to the Germans, their traditional queue was twisted so tightly that it protruded straight out from beneath their headgear, resembling a skillet handle.

The Jaeger units carried special short rifled muskets and were skilled at skirmishing in the rough American terrain. Most were hunters from Germany and excellent marksmen. They wore dark green jackets and hunting-style hats. The grenadiers, easily recognized by their tall miter hats, were the tallest of the soldiers. German troops, especially from Hesse-Cassell, were notably powerfully built.

The Hessian artillery used three-pounder cannons—called that because they fired three-pound balls. These lighter cannons supported the infantry and were easier to manage in America’s dense forests. A key event during the Americans’ attack on the Hessian Garrison at Trenton in December 1776 was a fight over one of these cannons. Over one thousand Hessian soldiers were captured during this struggle, which arguably prevented the American cause from ending that winter. This story is mentioned in book two of the Yankee Doodle Spies, The Cavalier Spy.

How they fought

Well, they fought valiantly. The German regiments were disciplined, capable of enduring great hardship, highly trained, skilled, and most importantly brave. Despite the tough conditions of their enlistment and the strict discipline they faced, they had great elan and esprit de corps. They took pride in their profession and disliked losing. In fact, they always believed they would win. The Germans were well equipped with the best weapons of the time and fought in disciplined companies of forty to eighty men.

These companies usually formed part of a regiment, often named after its commander or place of origin. With highly professional officers and non-commissioned officers, the Germans made a dependable force with combat effectiveness that exceeded their numbers. German regiments rarely failed to make a significant impact on a battle. They led the attack at the passes on Long Island and stormed Fort Washington's outer works. Their reputation was such that their presence near Washington's army helped pin the American front at Brandywine while the rebel flank was turned upstream. I could go on.

|

| Hessians adapted well to combat in America Jaegers skirmishing |

Who led them

The German officer corps, both commissioned and non-commissioned, was outstanding. They led from the front, and many fell in combat—most famously Colonel Johann Von Rall, who was mortally wounded while trying to rally his regiments for a counterattack after the Continental Army surprised them at Trenton. Another noted Hessian officer was Colonel Carl von Donop, who fought in many battles during the war until he was killed leading an assault at the Battle of Red Bank in 1777.

The commander of the Hessian forces was Wilhelm, Reichsfreiherr zu Innhausen und Knyphausen. He took over from the original commander, Von Heister, who commanded the Hessian troops effectively if not with distinction. After the disastrous Hessian defeat at Trenton, for which Heister, as corps commander, bore the ultimate responsibility, the old and ailing general was called back to Hesse in 1777. It’s worth noting that Heister clashed with Howe over strategy.

Unlike other British generals, he could be pretty blunt with the commander-in-chief. This might have also contributed to his return. Knyphausen remained the senior German officer for the rest of the war. He led the attack on Fort Washington, and one of the redoubts was later renamed in his honor. He also commanded the New York garrison but returned to Germany in 1782 for health reasons. General Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg succeeded him as commander of the Hessian troops in New York.

|

| Von Heister |

Legend and Legacy

Some might argue that the German contingent played a vital but not decisive role in the war. Still, it is hard to see how Britain could have raised as many quality regiments at home to fill the gaps if the Teutonic regiments hadn’t been there. The widespread use of hired foreign troops fueled the Americans' worst fears and prejudices, helping newspapers, pamphlets, and rumors spread myths about these unfamiliar invaders, all to rally the people in what was ultimately a war for hearts and minds.

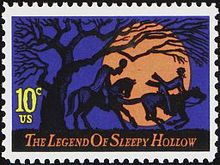

While the Hessians did act harshly toward civilians in some cases, many stories were exaggerated or amplified to stir up public sentiment. They were brutal to rebels during combat and treated prisoners more cruelly than the British did, but not more harshly than American Loyalists and Patriots treated each other. These myths and legends grew and still persist. It’s no coincidence that Washington Irving's famous "Headless Horseman of Sleepy Hollow" was a Hessian artilleryman whose head was taken by a cannonball. However, it’s also true that the Hessians were brave and dependable soldiers who added a unique element to the American fight for independence.