A little-known Hessian Colonel named Johann Gottlieb Rall played a significant role in the course of the American War for Independence. Sadly for him, that course led to his defeat and death. However, this should not diminish the life and service of this German military officer. An experienced Hessian officer, Rall is often portrayed as the unlucky loser of the Battle of Trenton. But he was much more than that. He was the quintessential professional German officer of the mid-18th century: skilled and confident, built from experience.

Advancement

Johann Rall was born in the German principality of Hesse-Kassel in 1720. His father was a captain in the regiment Von Donop. At an early age, the younger Rall joined as a cadet, then became a warrant officer, and finally was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant on August 28th, 1745. Within eight years, he had become a captain and was then promoted to Major on May 7th, 1760, under the command of Major General Bischhausen. In January 1763, he was transferred to the garrison at Stein, where he was appointed Lieutenant Colonel.

On April 22, 1771, now a Colonel, he took command of the Mansbach Infantry Regiment, a renowned unit. Unlike the British army of that time, officers were promoted based on merit rather than by purchasing their ranks. On his path to becoming a colonel, Rall likely served as a platoon leader, a company commander (possibly multiple times), and a staff officer, probably as an adjutant. By age 51, he was a highly experienced and professional military officer—perhaps among the best of his generation.

Early Service

So where did Johann Rall serve to reach the high ranks of regimental command? Actually, Rall's service is almost a detailed record of the wars in the mid-18th century. He fought in the War of the Austrian Succession - taking part in campaigns from the Low Countries of Flanders, through the Rhineland, and in Bavaria.

|

| A youthful Rall fought in the War of the Austrian Succession |

He even served in Scotland during the Jacobite rising of 1745 – not his last service to the German kings of England. Here, Rall was part of a group of about six thousand Hessian troops under the command of their prince, the Elector, Frederick II, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel. Frederick deployed his forces to support his father-in-law, George II of England.

|

| The battle of Culloden ended the Jacobite Rising |

Of course, Rall was there when the big one broke out. Like nearly all European professional soldiers, he saw action in numerous battles during the Seven Years' War (America’s French and Indian War). This global conflict was fought between 1756 and 1763 and involved every major European power. It spanned five continents, affecting Europe, the Americas, West Africa, India, and the Philippines. The war involved two main coalitions, one led by Great Britain (along with Prussia, Portugal, Hanover, and smaller German states like Hesse-Kassel), and the other led by France (with allies Austria, Russia, Spain, and Sweden).

|

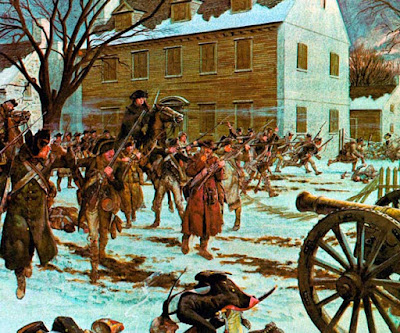

| Storming a village in the Seven Years War |

Most of the professional armies in Europe experienced a period of peace after the Treaty of Paris of 1763 ended the French and Indian War/Seven Years' War. However, Rall managed to stay busy in his chosen profession. From September 1771 to August 1772, he fought for Russia’s Catherine the Great under Count Orlov in the Russo-Turkish War.

|

| The Russo-Turkish War of 1771 was one of many fought between the two empires |

Coming to Amerika

What makes Johann Gottlieb Rall interesting to the Yankee Doodle Spies is his role as a Hessian officer in His Majesty’s service during the American War for Independence. Upon his return to Germany, Rall received command of a grenadier regiment that bore his name. In 1775, Landgrave Frederick Wilhelm II offered to “rent” several of his professional regiments to the King of England. It is said he used the revenues from such ventures to pay for his patronage of the arts. I guess it was blood for beauty. And so Rall and the regiment bearing his name embarked for America with a division of German troops under General Wilhelm von Knyphausen.

Knyphaussen’s forces were part of British Major General William Howe’s army that invaded Staten Island, Long Island, New York (Manhattan), Westchester, and the Jerseys in 1776. Rall was noted for his performance under fire on Long Island and again at Fort Washington, where Knyphausen’s Hessians distinguished themselves with audacity, skill, and courage.

|

| Rall's Grenadiers storm a redoubt at Fort Washington |

At Fort Washington, Rall led the final assault from the front. One of his men, Private Johann Reuber, recalled him encouraging the grenadiers, "All that are my grenadiers, march forward." Leading the charge, Rall’s grenadiers captured their objective. His grenadiers lost 177 men in the action, a large number of casualties for the period, and a tribute to their courage and audacity, as well as Yankee marksmanship.

Most of these battles were against raw, undisciplined, and poorly supplied troops, although not always. It didn’t take long for the Hessians and Rall himself to come to see the rebellers as beneath respect. In fact, many Hessian officers were perplexed that Howe didn’t strike the "rabble" more aggressively to destroy them. Howe’s slow, careful style of warfare clashed with the aggressive, smash-mouth approach of the sharp German troops and their leaders.

Blitzkrieg turns to Winter Quarters

As General George Washington led his battered army across the cold, snowy New Jersey in December 1776, it seemed like the war was nearly over. The Germans, along with many British officers, believed it was only a matter of days before they would crush Washington and seize the rebel capital. To their disappointment, Howe decided he had done enough for the year. He settled his army into winter quarters, confidently expecting an easy march to Philadelphia in the spring. After all, the rebels had been driven across the Delaware with their tails between their legs, and the morale of the American people was at an all-time low. He was right, too—except for one small problem: General Washington was not in winter quarters.

|

| Gen William Howe put his army into winter quarters a bit too early |

Howe compounded his mistake by dispersing his forces into small garrisons across West Jersey, including Perth Amboy, New Brunswick, Princeton, Trenton, and Bordentown. The weather and the appealingly small, brigade-sized garrisons gave the beleaguered American commander the opportunity he needed. He planned to strike the closest garrisons: Bordentown and Trenton. Bordentown proved to be a missed opportunity, but Trenton was not.

The approximately sixteen hundred Hessians comprising Trenton’s garrison had been under pressure. The Jersey militia had rallied against them. Couriers, patrols, and foraging efforts were attacked. Rall’s officers recommended they fortify Trenton. The town had a comfortable barracks where the troops stayed, but aside from an isolated blockhouse north of the town, they had nothing else. Despite Rall’s professionalism, his contempt for the Americans was evident. He dismissed the suggestions as unnecessary, and he actually stated he dared the Americans to attack so he could crush them. This was not just hubris but a cold, professional calculation. However, it would turn out to be a poor one.

|

| The Trenton garrison had some of the best infantry of any army of its day |

Rall also dismissed the engineer officer sent to help with the defenses. He simply believed his men would overpower any rebel force that approached Trenton. Rall claimed he could be attacked from all sides and would defend from every direction. No redoubts were necessary. However, he did increase patrols, some of which he led himself.

As Christmas neared, British intelligence received word from a spy that the Americans might be planning an attack on Trenton. The British commander in the Jerseys, General James Grant himself, was skeptical of a rebel assault. However, he sent a note to Rall to warn him anyway. Rall scoffed at the idea and dismissed it as alarmist. Besides, he had complete faith and trust in the professionalism of his men and the incompetence of the enemy. The former is usually a good thing; the latter, not so much. Rall stuffed the note in his pocket.

|

| Washington launches his gambit on Christmas Night |

Heilige Nacht

Now, in the German world, Christmas Eve is a very big deal—more than Christmas Day. How much “celebrating" actually took place is open to some speculation. Likely, some did. But the real problems the Hessians faced were the weather, the Jersey militia, and frankly, some fatigue. The campaign had been long.

Rall spent Christmas Eve at the Stacey Potts house in Trenton. Unbeknownst to him, his officer of the day, Major Friedrich von Dechow, canceled the next morning’s dawn patrol due to the bad weather. Other officers ordered their troops in outposts to shelter in place as the weather moved in. It was, as they say, a perfect storm. Washington struck Trenton in a surprise early morning attack on Christmas Day 1776. Washington’s 2400 men outnumbered the 1600 defenders. But numbers were not the decisive factor- surprise was.

|

| The Americans depended on the cover of darkness and bad weather to fuel their surprise |

The Element of Surprise

Just after sunrise, one of the Hessian officers sheltering near the outskirts of Trenton, Lieutenant Andreas von Wiederholdt, stepped out of the building he had taken cover in and was surprised to see rebels emerging from the woods around the town. He rallied his platoon and exchanged fire with the approaching troops, but was quickly overwhelmed. By the time the alarm was finally sounded, Trenton was already surrounded on three sides.

Artillery rounds from Henry Knox’s battery began to bombard the town. The Americans had occupied several houses, and as the infantry tried to rally, they were picked off. In the wet snow, the Hessians' return fire was hard to manage due to wet powder and flints.

|

| Knox's Artillery suppressed the Hessian attempt to counterattack |

Surprised, outnumbered, surrounded, and overwhelmed by firepower, the defenders faced a bleak situation. But Hessian discipline was still strong. What you do in training, you will do in combat. The Hessians were well trained. Drummers quickly started beating, and Rall’s regiment rallied. Officers signaled to form ranks. Sergeants and corporals organized the men into lines. Some were only partially dressed or missing some equipment, but they still formed up.

|

| Washington's pincer movement almost bagged the entire garrison |

Commands were shouted over the crack of musket shots. But confusion began to turn into order when Rall appeared. He looked tired, some say in his cups, but this is unproven. Rall struggled to mount his horse and rally the troops for a charge that would disperse the rebels like chaff from a scythe. That is how they always did it. They would do it again.

At Fort Washington, Rall summoned his grenadiers to advance with him. They did, and two of the three regiments formed ranks, moving forward with colors flying and drums beating. They would disperse the rebels yet. But this was a different army—well-led and motivated. More importantly, the advancing formation was enfiladed from three sides by Continental infantry firing from behind the cover of houses and artillery bombarding them from the flank. The wet snow limited their return fire, and cold steel alone wouldn't be enough today. Still, they pressed on toward the enemy. "Nach Vorne!"

|

| The American infantry surpassed the crack Hessian regulars |

At that critical moment, a musket ball struck Rall in the side. He jerked but managed to turn his horse around and tried to raise his saber. Then a second shot hit him. Rall fell, mortally wounded. Seeing their commander shot from his horse, the usually steadfast Hessian infantry retreated into an orchard and tried to reform once more. Rall was taken to a nearby church and eventually back to Stacey Potts' house. He died there that night.

|

| Rall was stuck down at the critical moment |

Determined, Washington had his men fire into their ranks while Knox’s guns tore through them with round shot. Men were falling. Having just seen their beloved commander carried off, morale quickly began to fade. At first, the Hessians refused calls to surrender. Washington was about to tell Henry Knox to switch to canister – which would have torn through the Hessian ranks like a 12-gauge round through a flock of fat geese. But the grim work was not to be. Always professional, the Hessians realized it was over and began to ground their arms in surrender. Aside from a few hundred who fled across the Assunpink River, the Trenton garrison was captured by the ragged rebel forces led by General George Washington.

|

| After he was struck down, Rall's men forced to surrender to die Rebellen |

What of Rall?

Was Johann Gottlieb Rall an arrogant Teuton and drunk, whose hubris cost him his command, his life, and most importantly, his reputation? As is often the case, the verdict is mixed. Rall was well respected by his men. In an army where blind obedience to officers and NCOs was required, respect was not. And he had their respect. Even more remarkable, Rall was liked by his men.

|

| Rall in better times |

A noted war diarist and Rall's adjutant at Trenton, Lieutenant Jakob Piel, writes, “Considered as a private individual, he merited the highest respect. He was generous, magnanimous, hospitable, and polite to everyone; never groveling before his superiors, but indulgent with his subordinates. To his servants, he was more of a friend than a master. He was an exceptional friend of music and a pleasant companion."

Note that Rall was outspoken with his superiors. Few had his combat experience. The brutally frank Rall made sure they knew it. Fellow Hessian Colonel Carl von Donop treated Rall with contempt. However, Captain Johann Ewald of the Jaegers, who later rose to the rank of Lieutenant General, claimed that when it came to fighting, none of the other German officers were fit to carry Rall’s sword. British Colonel William Faucitt considered Rall “... one of the best officers of his rank in the Landgrave’s Army."

Goat? Or Scapegoat?

|

| Friedrich Wilhelm II - not pleased |

Rall’s ruler and commander in chief, Prince Frederick Wilhelm II, convened a court-martial to determine what had happened to his proud army at Trenton. It was bad for business if the Hessians were seen as easy targets for undisciplined troops. Predictably, the court blamed the defeat on Rall and four of his officers. Since they were now dead, there was no real defense made. Colonel Rall was found "guilty" of not fortifying Trenton.

However, the truth is that fortifications would have been of little help, as most of the men were sheltering from the weather. Additionally, the Americans had superiority in artillery. Not surprisingly, all the surviving Hessian officers were conveniently cleared of wrongdoing. Of course, a Hessian court could not address the larger factors in the defeat: Howe’s dispersal of small garrisons in a hostile region and Grant’s inability to support the forward garrisons, who faced constant rebel militia pressure. Colonel Johann Gottlieb Rall was not completely blameless, of course – but he took the blame for the whole thing.

Yankee Doodle Postscript

Actually, a shameless Yankee Doodle Spies plug—my second novel in the popular Revolutionary War espionage series—concludes with all the events surrounding the campaign leading up to and including the Battle of Trenton. I take some liberties with dialogue and certain scenes, but not with the actual historical events. I believe I captured Rall pretty well as part of the story.