Okay, sue me. I’m the king of bad puns. But today, August 10th, is Lord Howe's birthday, so let's move on to the main topic. With a formidable professional army, paid German mercenaries (the world's better fighters), a large Loyalist following, real money, and the best navy in the world—how could Lord William Howe lose his job and set a trend that led to an impasse and eventual defeat by the pitiful rebels in America? Howe took command of British forces in Boston in 1775, replacing General Gage, whose failures included Concord and Bunker Hill. Howe's leadership shaped British actions from then until his recall in early 1778. When his reinforcements arrived, he commanded the largest force England ever sent to America during the trying times that tested men's hearts.

|

| William Howe |

Let's examine William, the 5th Viscount Howe, before discussing his death. We can begin with his background. William Howe was born on August 10, 1729, to the 2nd Viscount Howe and Charlotte Von Keilmansegg, daughter of the Countess of Leinster and Darlington. This connection helped launch him and his two brothers into notable military careers. But it gets better—his grandmother was the illegitimate daughter of King George I, making him a cousin to George III. Whether illegitimate or not, connections—including land and titles—carried significant weight in Georgian England. Howe and his brothers served their kinsman, King George II, during the Seven Years’ War (the French and Indian War).

William rose to command the 58th Regiment of Foot as a lieutenant colonel. To say he served bravely and effectively is an understatement. At the siege of Louisbourg in Nova Scotia, he led an amphibious landing that earned him praise. Howe's greatest achievement in the war (though not his last) was leading a force of elite light infantry up a steep, narrow trail that climbed the cliffs overlooking the St. Lawrence River. His bold move under the cover of darkness surprised the French and helped General Wolfe's army defeat the Marquis de Montcalm on the Plains of Abraham outside Quebec. This victory ultimately placed French Canada under British rule. Later in the war, Howe achieved further successes in Canada, France, and Cuba.

Howe's brother George, a general, died during the French and Indian War, and William took his seat in Parliament in 1757. His politics were, as they said back then, "Whiggish." The Whig party, while not as liberal as today, supported limits on the King's authority. He was sympathetic to many American grievances and kept that sympathy throughout the American War for Independence. When he assumed command of the British forces besieged in Boston, Howe was promoted to lieutenant general in January 1776.

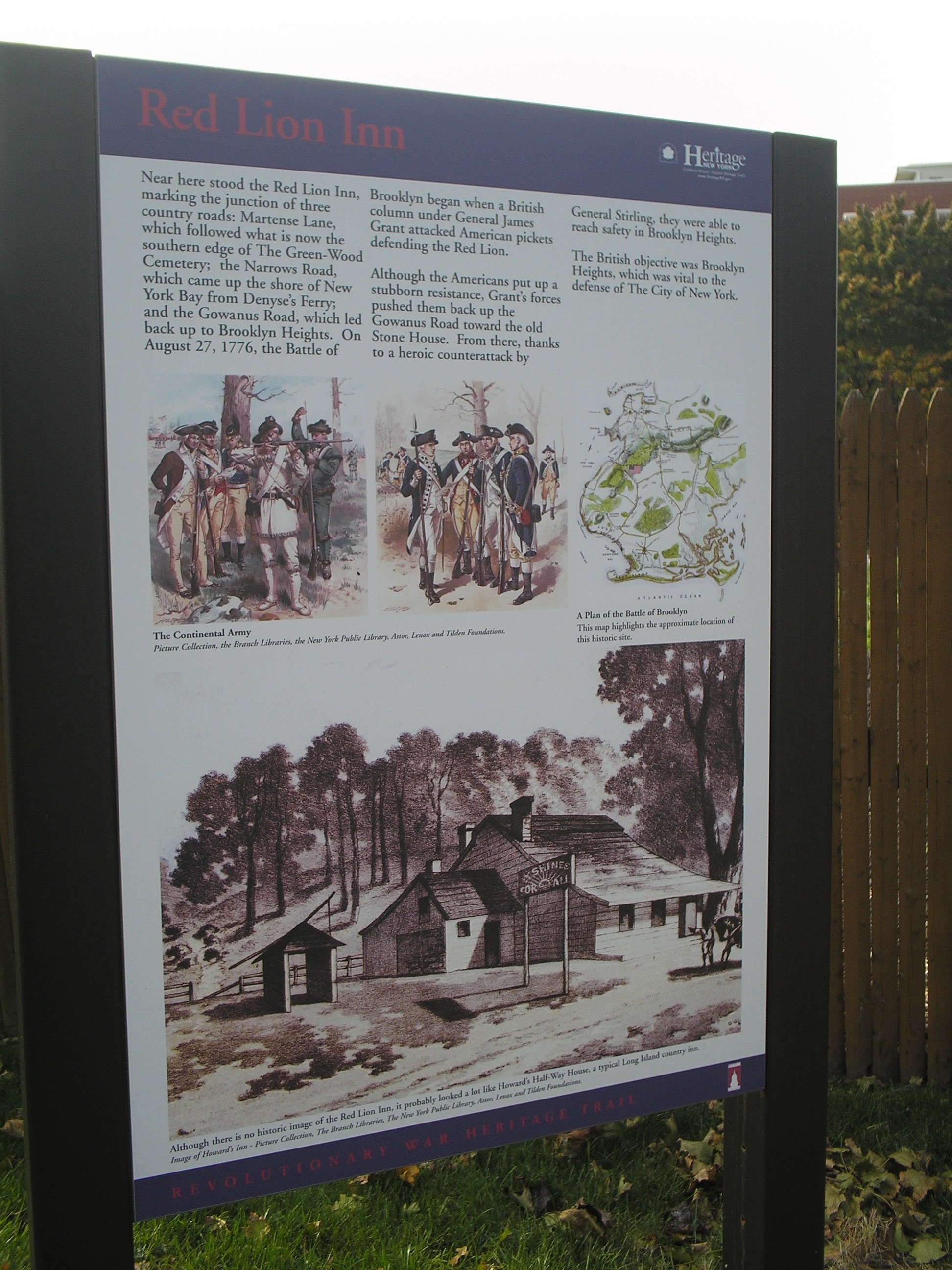

Howe was a thorough planner and understood tactical, operational, and strategic warfare better than most of his peers. He was well helped by his equally wise brother, Admiral Richard Howe. Richard, called "Black Dick" by Royal Navy sailors because of his dark complexion, was a daring and charismatic leader. With more reinforcements on the way, the Howes started a strategy to isolate New England from the other colonies instead of trying to conquer it. A large naval maneuver moved his forces to Newport, Rhode Island, and from there launched an "envelopment from the sea" on New York, through Staten Island and Long Island. This campaign served as the background for my novel, The Patriot Spy.

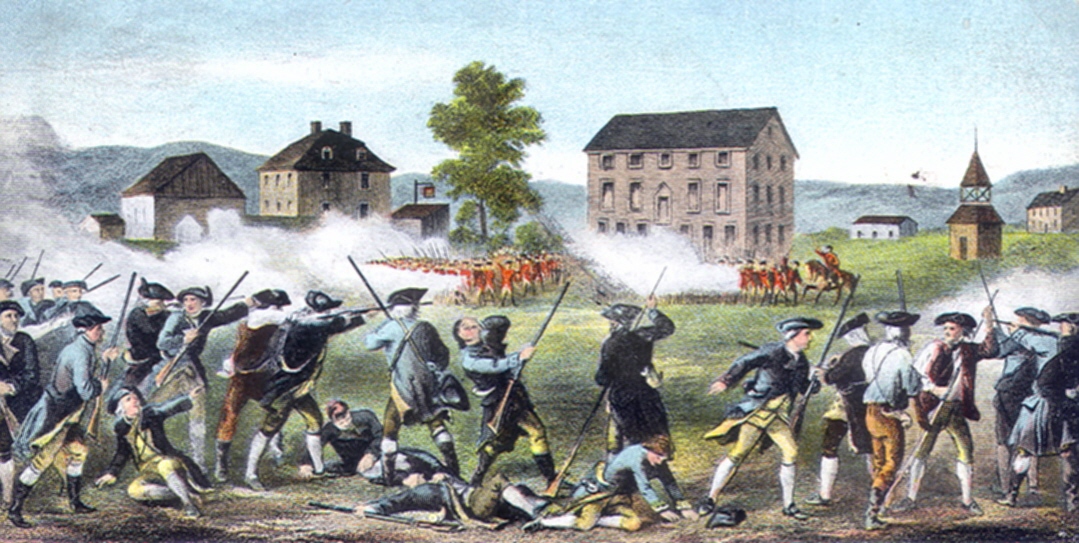

The Howe brothers organized multiple amphibious landings, sieges, and sweeping flanking maneuvers under cover of darkness, and they won several pitched battles. Truly, a masterwork of combined arms warfare in 18th-century style! Howe eventually took New York and pushed Washington's army across the Jerseys in a blitzkrieg-like manner.

Howe liked Americans (but not rebels), so in the Jerseys, Howe's whiggish tendencies led him to attempt a clumsy form of rehabilitation that, had it succeeded, might have ended the war. But it didn't, and his grand maneuvers, successful assaults, and (not so) hot pursuits ultimately failed. To top it off, Howe's decision to move south in his own campaign against the rebel capital at Philadelphia sealed General John Burgoyne's fate at Saratoga in 1777, which proved to be the turning point (sorta) in the war.

Howe liked Americans so much he took one as his mistress. Mrs. Elizabeth Loring was the beautiful young wife of Loyalist schemer Joshua Loring, who traded his wife's charms for a position as Commissary for Prisons, a post that offered Loring opportunities for graft at the expense of his charges. The starvation and disease that plagued American prisoners throughout the war attested to that fact. Howe's interest in his amiable companion led to accusations that she was causing him to linger so long that victory might slip away from the grasp of the victorious British. Many ribald poems and ditties were crafted by citizens and soldiers to celebrate the affair and poke fun at Howe.

One such ditty went...

Sir William he,

snug as a flea,

Lay all this time a snoring,

Nor dreamed of harm

as he lay warm,

In bed with Mrs. Loring.

And another...

Awake, arouse, Sir Billy,

There's forage on the plain.

Ah, leave your little filly,

And open the campaign.

So where did Howe fail? Simply put, he was not a closer—except, it seems, in bed. He also lacked the respect of his two main subordinates, Charles Cornwallis and Henry Clinton. Howe sometimes moved at a sluggish pace. The blitz across New Jersey was led by the vanguard under General Cornwallis. Throughout Howe's campaigns, Cornwallis and Clinton often chafed and complained that Howe was missing decisive follow-up.

Howe's slow approach repeatedly allowed George Washington's forces to escape. Confident of victory, Howe preferred a steady, methodical approach, hoping to reconcile the rebels. Although he outmaneuvered and outfought Washington from New York to Philadelphia, he never managed to defeat him completely. Washington endured two harsh winters, fearing Howe would attack his weakened Continental Army, but he ultimately escaped.

|

| Henry Clinton |

The surrender of Burgoyne's army sent shockwaves from Horse Guards to Hampton Court. Parliament erupted in reaction. Maintaining professional armies was expensive, and the Royal Treasury had its limits. Sensing the pressure, Howe resigned as the winter of 1777-78 drew to a close. His occupation of Philadelphia offered no strategic benefit to the British war effort, and Lord George Germain, the Minister for the Colonies, accepted his resignation. With Charles Cornwallis back in England to care for a sick wife, General Henry Clinton was set to take command.

The story ends in a strange way. Howe was sent off with a wild and costly farewell party called the "Mischianza." This was a Bacchanalia-like mixture of music, plays, exotic costumes, and women dressed in elaborate outfits. The event concluded with a grand revue featuring fireworks and plenty of food, drink, and merrymaking. The organizer was Major John Andre, who would later become known for recruiting the spy, Benedict Arnold. Many British officers attending the Mischianza thought it was an over-the-top display of luxury during a wartime period of hardship. Sir William Howe went back to England and held a series of pretty unremarkable positions until he died in 1814.